The new buyers behind long-haul gas pipelines

After years of free-riding, LNG developers and power generators are beginning to underwrite interstate capacity

Meeting the next decade of U.S. gas demand growth — from LNG expansions and accelerating power loads — requires someone other than producers to pay for long-haul transmission.

But outside the Southeast, that “someone” didn’t exist. Producers carried the risk until it became commercially untenable, at which point new transmission development shifted to shorter intrastate routes. Even as demand kept rising, LNG buyers and power generators free-rode on capacity paid for by producers and gas utilities.

Now, the pattern is shifting: LNG developers contracting further upstream, and power generators outside the Southeast beginning to backstop expensive greenfield interstate transmission.

LNG developers

Since 2017, six new large-scale1 LNG facilities have come online, five of which are located between Corpus Christi and Lake Charles.

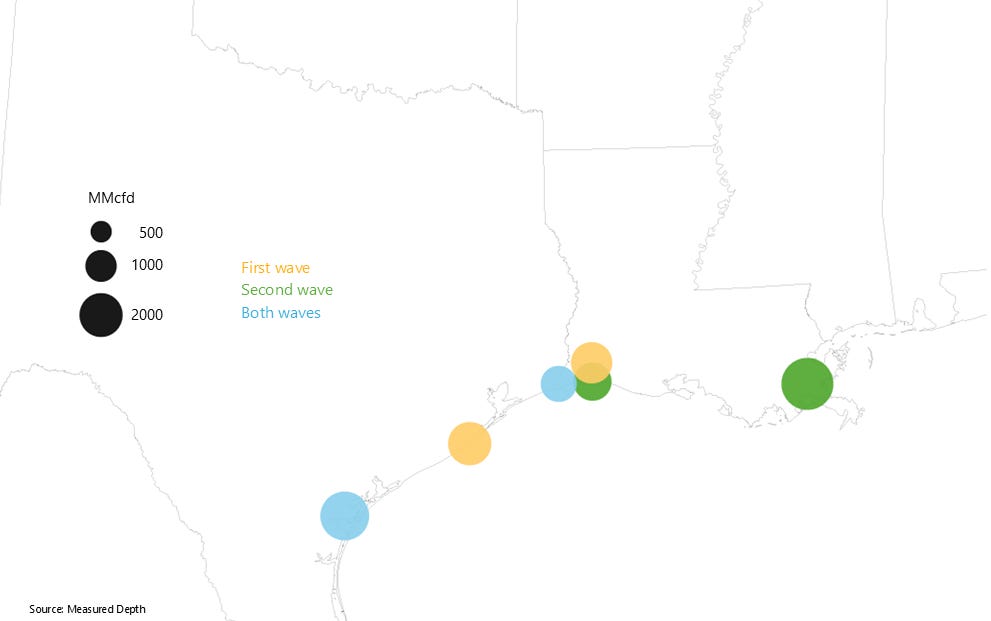

Figure 1 | Large-scale LNG capacity additions since 2017

That corridor benefitted from proximity to the Haynesville, Permian, and Eagle Ford, from which producers could afford to underwrite relatively inexpensive takeaway to the coast. Haynesville operators underwrote LEAP, LEG, and NG3, all of which deliver to the Gillis area in southwest Louisiana. Only two LNG developers took out significant new-build upstream capacity:

The vertically integrated Golden Pass project2 backstopped Gulf Run Pipeline, which sources Haynesville gas directly.

Cheniere’s Corpus Christi Liquefaction contracted for 300 BBtu/d on the ~1.1 Bcfd Midship Pipeline. Cheniere holds an extensive transport portfolio, but its other upstream positions are smaller or on cheaper expansion/reversal projects.

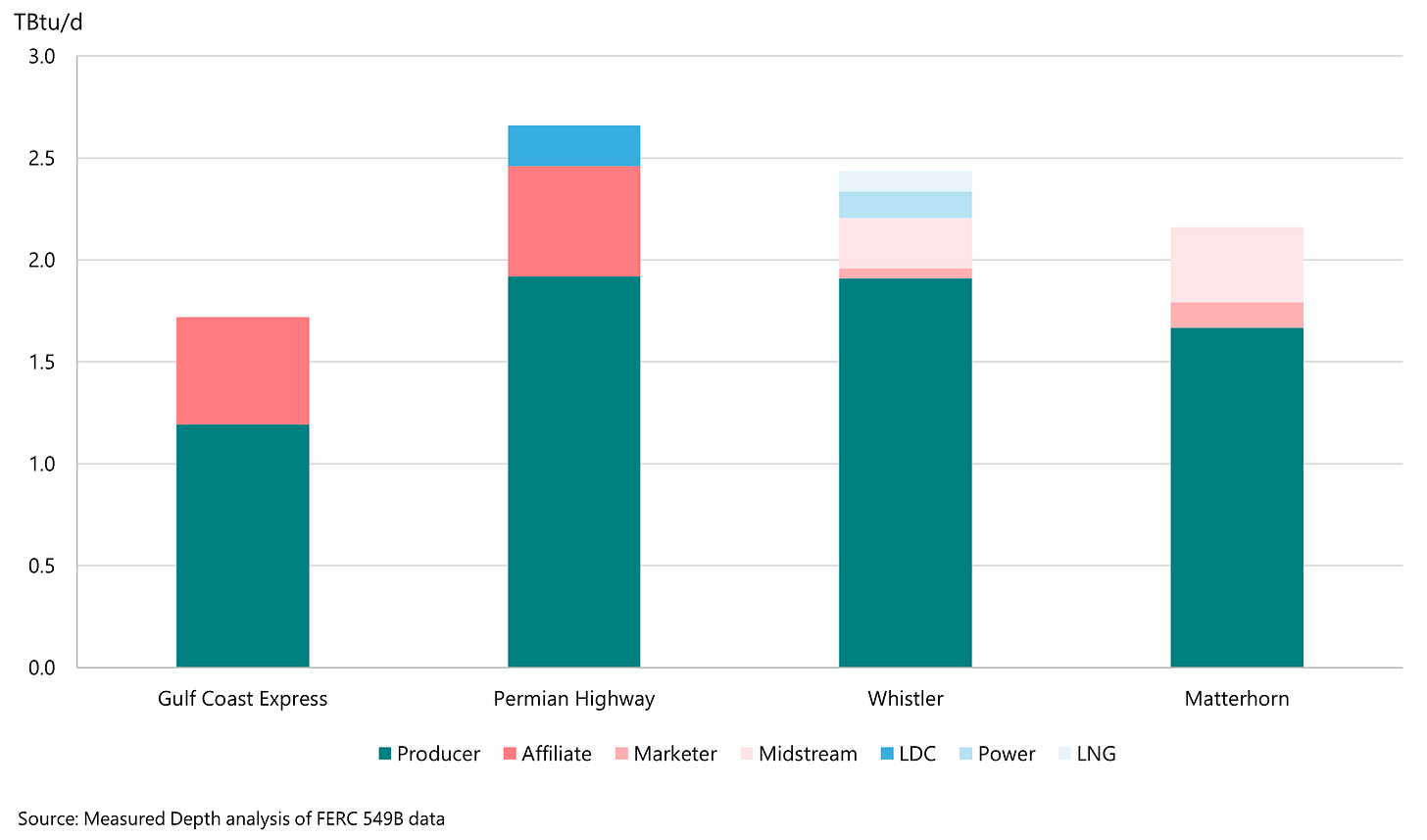

Meanwhile, Permian producers backstopped four major pipelines — Gulf Coast Express, Whistler, Permian Highway, and Matterhorn — to southeast Texas.

Figure 2 | New-build Permian pipelines by shipper type

But that model only works for LNG buyers as long as producers are bringing the gas nearby. Producers did not build capacity proximate to Plaquemines LNG, so while that facility held sufficient downstream capacity to ensure deliverability, its ramp-up pushed TGP 500L basis differentials to as much as a $0.50/MMBtu premium to Henry Hub.

New projects indicate a shift: Energy Transfer noted last year that Hugh Brinson shippers were weighted toward consumers rather than producers. And with more than enough Permian gas takeaway under construction to accommodate likely associated gas growth, I expect that the recently upsized 3.7 Bcfd Eiger Express is at least two-thirds backed by consumers.

Venture Global has also taken a different approach for CP2, as the sole shipper on Blackfin Pipeline, which delivers gas from the terminus of Matterhorn Express near Katy to CP Express Pipeline.

Power generators

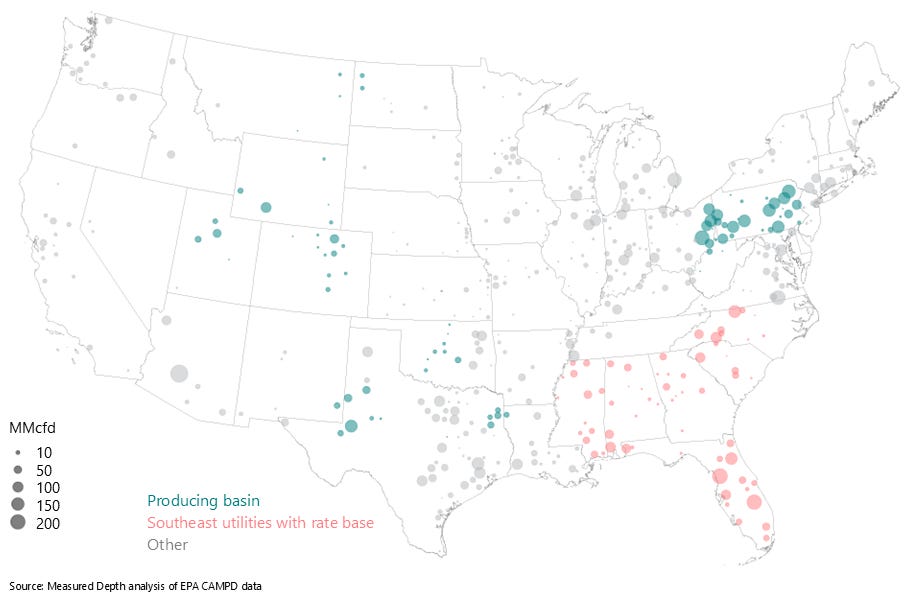

Gas-fired generation has grown nationwide since 2017, despite very uneven pipeline development. Vertically integrated utilities consistently contracted for long-haul gas pipeline capacity, facilitating ~1.7 Bcfd of growth. An additional ~2.7 Bcfd of growth came in and around gas-producing basins, where no significant transmission investment was needed.

But ~5.8 Bcfd came in the rest of the country, where merchant generators relied on capacity paid for by producers or gas utilities, because deregulated power markets lack cost-recovery mechanisms for firm pipeline commitments.

Figure 3 | Gas-fired generation growth since 2017

Now, the primary driver of growing gas-fired generation has shifted: from coal displacement to data centers. Southeast utilities are again backing major new projects — Transco’s ~1.6 Bcfd Southeast Supply Enhancement, Gulf South/Texas Gas’s ~1.2 Bcfd Koscuisko Junction, and TGP/Sonat’s 2.1 Bcfd Mississippi Crossing — but we now see commitments emerging elsewhere.

Power-backed Permian projects

Last year’s Blackcomb and Hugh Brinson FIDs resolved a medium-term Permian gas takeaway constraint, especially with WTI trading at less than $60/bbl. Nonetheless, Permian midstream operators made three major announcements this year:

Tallgrass’s May announcement of a new Permian-to-REX pipeline, with sufficient precedent agreements to proceed

Energy Transfer’s August FID of the 1.5 Bcfd Desert Southwest expansion of Transwestern, explicitly backed by Arizona utilities

WhiteWater’s August FID on the 2.5 Bcfd Eiger Express, likely backed predominantly by LNG buyers and now upsized to 3.7 Bcfd

Historically, Permian producers backstopped less-expensive interstate expansions and new Texas intrastate projects. These new Texas intrastates typically cost $2-3 billion, translating into reservation rates of $0.40-0.60/MMBtu. Transwestern’s Desert Southwest expansion, in contrast, is projected to cost $5.3 billion for only 1.5 Bcfd, implying rates of ~$1.50/MMBtu.

This project, in contrast, is backed by power buyers. Salt River Project and Arizona Public Service announced precedent agreements; Energy Transfer reported the project was oversubscribed and may be upsized. Phoenix is a locus of data center development, and gas-fired generation is growing quickly. In Maricopa County alone, SRP’s gas-fired generation has doubled since 2017.

In the Rockies, Tallgrass is partnering on a massive data-center development in southeast Wyoming. The 1.8 GW site is designed to scale up to 10 GW, requiring more than 1 Bcfd of gas at full buildout. Although I am curious about how the long-run economics of expanding REX to source these volumes from the Rockies or Appalachia3 compare to those of developing a new right-of-way from the Permian,4 the signal is clear: power generators are now willing to pay for long-haul capacity.

What remains unclear is the exact mechanism: data centers don’t have a rate base, but they are typically backed by much bigger balance sheets than merchant generators. I expect that, in conjunction with the Arizona utilities’ contracting for this Desert Southwest capacity, they also have some form of guarantee in place with the data centers on their systems.

Implications for producers and midstream operators

LNG buyers will continue leaning on the most proximate basins — Haynesville, Permian, and Eagle Ford — until they fail to deliver. But unlike the last eight years, they are beginning to contract further upstream and assume some of the risk producers bore overwhelmingly.

Data-center development, meanwhile, is accelerating and likely to benefit Appalachian operators disproportionately. By building in Appalachia, developers access far more economic gas supplies than in regions where they compete with LNG buyers. But electric transmission losses mean that data center development needs to be geographically dispersed. In the medium term, power-backed transmission development from Appalachia to the nearby Midwest and Deep South looks increasingly likely, as does expansion of gas pipeline capacity from the WCSB to the Pacific Northwest or the northern Plains.

In short, with under-utilized infrastructure increasingly scarce and producers stepping back from transmission development, LNG buyers and power generators are emerging as major shippers — accelerating gas infrastructure development and reshaping its commercial model.

Cove Point and Elba also came online on the East Coast, but both are much smaller than all the Gulf Coast liquefaction plants

Not shown on the map because it is not online yet, although Gulf Run is

Tallgrass recently held open seasons for both of these, albeit much smaller in scale — likely compression expansions — than the new pipeline from the Permian

Especially accounting for what all of this coincident pipeline development could do to Waha basis differentials