Why I'm bullish on Henry Hub

The market still sees persistent oversupply as the natural state of U.S. gas, but the underlying forces have reversed

The market1 is still anchored to a 2010s mindset — a belief that low-cost gas is plentiful. That psychology made sense then, but it doesn’t now. And that backward-looking mindset is now the single biggest reason the forward curve is mispriced.

When I began as a North American gas analyst in 2008, the Haynesville was barely on the map, the Rockies were still the center of unconventional gas, and the Marcellus was largely untested. Tight oil didn’t exist; the Barnett, Woodford, and Fayetteville were the only real shale plays.

Over the following decade, one new low-cost supply source after another emerged, each pushing the supply curve down, faster than anyone could update their models. That’s why I spent most of the 2010s structurally bearish: each new play proved that a supply curve built from what we currently knew was already obsolete, and our price outlook already too high.

But that world is gone. The forces that kept surprising the market to the downside are no longer in place. In several cases, they’ve outright reversed.

Productivity trends are shifting the supply curve up

Since the Delaware ramped up in the mid-late 2010s, no new low-cost gas supply sources have been commercialized. Instead, productivity degradation outweighs continued improvements in drilling and completion efficiency. Today, producers run just ~40 Haynesville rigs at a ~$4.10/MMBtu two-year Henry Hub strip, down from ~55 rigs in early 2019, when futures traded at less than $3.2

Northeast pipeline development is nonexistent

By far the most significant force pushing 2010s gas prices downward was the commercialization of Northeast gas supplies. After reversing long-standing south→north flows, a next phase of Appalachian production growth came from reversals, allowing those same pipelines to instead move gas north→south. Because those pipeline projects involved re-piping compressor stations, they were cheap enough — typically $0.25-0.50/MMBtu — to be underpinned by producer shippers.

Once those reversals were exhausted, however, new-build development from the Northeast got much more expensive. MVP is the most obvious case, but the two other new-build Northeast takeaway pipelines — Rover and NEXUS — didn’t have years of court battles and were still very expensive. Built in much friendlier terrain, tariff rates on those two pipes are $0.93/MMBtu and $1.15/MMBtu, respectively.

At this level of demand charge, committing to 15+ years of capacity becomes a much tougher hurdle for producers, who are also exposed to commodity risk at the other end of the capacity. But with the long-dated strip at $3.65, committing to $1/MMBtu of demand is too big a pill to swallow. Instead, Northeast pipeline development has ground to a halt, limiting the amount of gas from the region that can meet future demand growth.3

Oil market trends are slowing associated gas growth

Oil demand growth is decelerating, meaning that offsetting global base declines and meeting oil demand growth now requires fewer wells to be drilled, ceteris paribus. And OPEC4 is withholding millions of barrels per day.

Regardless of what OPEC actually does, that potential OPEC hammer restrains how aggressively oil-weighted E&Ps develop their assets. Combined with deteriorating productivity and capital discipline, oil activity is likely to be weaker, at the same oil prices, than it was in the 2010s.

As the basin ages, rising gas-oil ratios will support a faster pace of associated gas production growth compared to oil production increases. But associated gas growth is unlikely to match the pace seen when oil prices traded at more than $100/bbl, and productivity in oil plays was still improving.

How the market misread the last five years

So we’re not going to get as much Northeast, Haynesville5 or associated gas as we did historically. But of those three, only the Haynesville has really changed in the last few years — why haven’t gas prices been high since 2019, when producers got religion on capital discipline? I would argue that the market has misread structurally bullish markets as cyclical and misread cyclically bearish markets as structural.

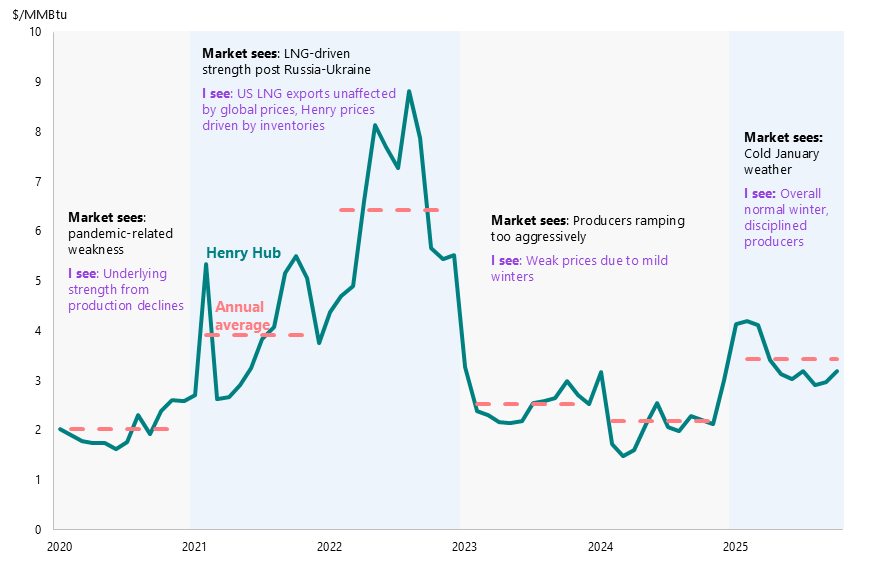

Figure 1 | Henry Hub prices

Sources: EIA, author’s annotations

What would change my thinking?

Currently, the 2026 strip trades at about $4.20/MMBtu, but the curve is backwardated, with 2030 trading at ~$3.65.6 Prices steadily marching upward from $4 toward $4.50/MMBtu later this decade is more realistic.

So yes, I am structurally7 bullish now. But I was always bearish in the 2010s, underpinned by the same meta-analysis of not just what’s in the supply and demand curves but also what’s not in them and could be. Changing that view, then, would require some combination of:

A step-change in technology that materially reduces the cost of supply. Possible, but more likely to come in nickels than in the quarters that would change the long-run Henry Hub outlook materially.

A resumption of large-scale Northeast pipeline development. Possible in a higher-price environment, but very unlikely at the current strip.

A new source of low-cost non-associated gas supply, most likely in the Permian. By 3Q26, new gas takeaway capacity will narrow Waha differentials sharply, likely prompting a shift to deeper, more gas-weighted Permian intervals. The open question is whether those intervals, in full development mode, constitute a new low-cost gas supply source or another resource that still requires $4+ Henry Hub prices to ramp up.

Short of those developments, the path for Henry Hub is structurally higher. But the market is still priced for the world we left behind. The forward curve will catch up — it always does — but it is still anchored to the wrong decade.

If you’re seeing this because it’s circulating in your inbox or Teams channel, you can subscribe directly at www.measureddepth.com.

The gas futures market to some extent but especially the equity market for gas E&Ps

Granted, improved drilling efficiency means this isn’t an apples-to-apples comparison

The cost of pipeline development affects Permian and Haynesville operators, too. With demand growth increasingly concentrated on the Gulf Coast, higher Henry Hub prices do not translate one-for-one into upside in realized prices for producers across the continent. Or put another way, part of being bullish Henry Hub prices is being bullish Henry Hub “basis,” if such a thing existed.

Indeed, not having to do OPEC Kremlinology is one of life’s underappreciated joys of being a gas analyst

At least at the same prices

Granted, the market is not very liquid that far out the curve, but this isn’t just about the lack of liquidity: when I talk to investors and other market participants, there’s broad skepticism that gas prices will be sustained above $3.50 or perhaps $4.00.

At least on a structural basis — weather and other transient factors have and will sometimes make me bearish on a seasonal or year-ahead basis

Excellent post. Thank you.

I note that there is no mention of Canadian LNG. Is this not relevant?

Historically, the US was effectively Canada's only customer for LNG exports. That gave the US strong pricing power which it largely exploited to is advantage.

The US economy was a beneficiary of cheap and plentiful LNG from north of the border.

But that's changed. Canada has now built the infrastructure that has enabled it to export LNG internationally and it is anticipated to become a major player in the global market.

This means that the US has lost it's pricing power and will need to pay more for it's LNG imports.

The Trump administration has also caused US/Canada relations to decline markedly, which does nothing to improve the situation.

I would imagine that this plays into your narrative of rising US gas prices going forward. I welcome your thoughts.

What about LNG oversupply,

potentially?