Antero’s HG deal resets the Appalachia playbook

What the deal signals for rich gas, dry gas, and the next phase of Appalachian growth

Antero’s1 two announcements Monday — buying HG Energy’s West Virginia assets for $2.8 billion while selling its own Ohio position to Infinity2 for $1.2 billion — look like a portfolio swap. But together, they answer two key questions for Appalachian gas: how Antero plans to keep pace with consolidating peers, and how the basin’s constrained future will shift the balance between rich gas and dry gas. The choice to acquire HG rather than expand Sherwood/Smithburg or grow its own dry gas hints at broader trends: a shift toward dry-gas acreage and to smaller operators’ proving up the next tier of inventory.

How Antero intends to keep up with growing peers

Antero’s long-haul FT strategy — once questioned,3 now thoroughly vindicated — remains central to its positioning. The downside of Antero’s FT capacity, though, is that it sources gas almost exclusively from its own upstream and midstream assets. In contrast with, say, EQT’s TETCO capacity, Antero can’t easily capture the value of its FT without also producing its own equity gas. Before this deal, this situation posed two challenges:

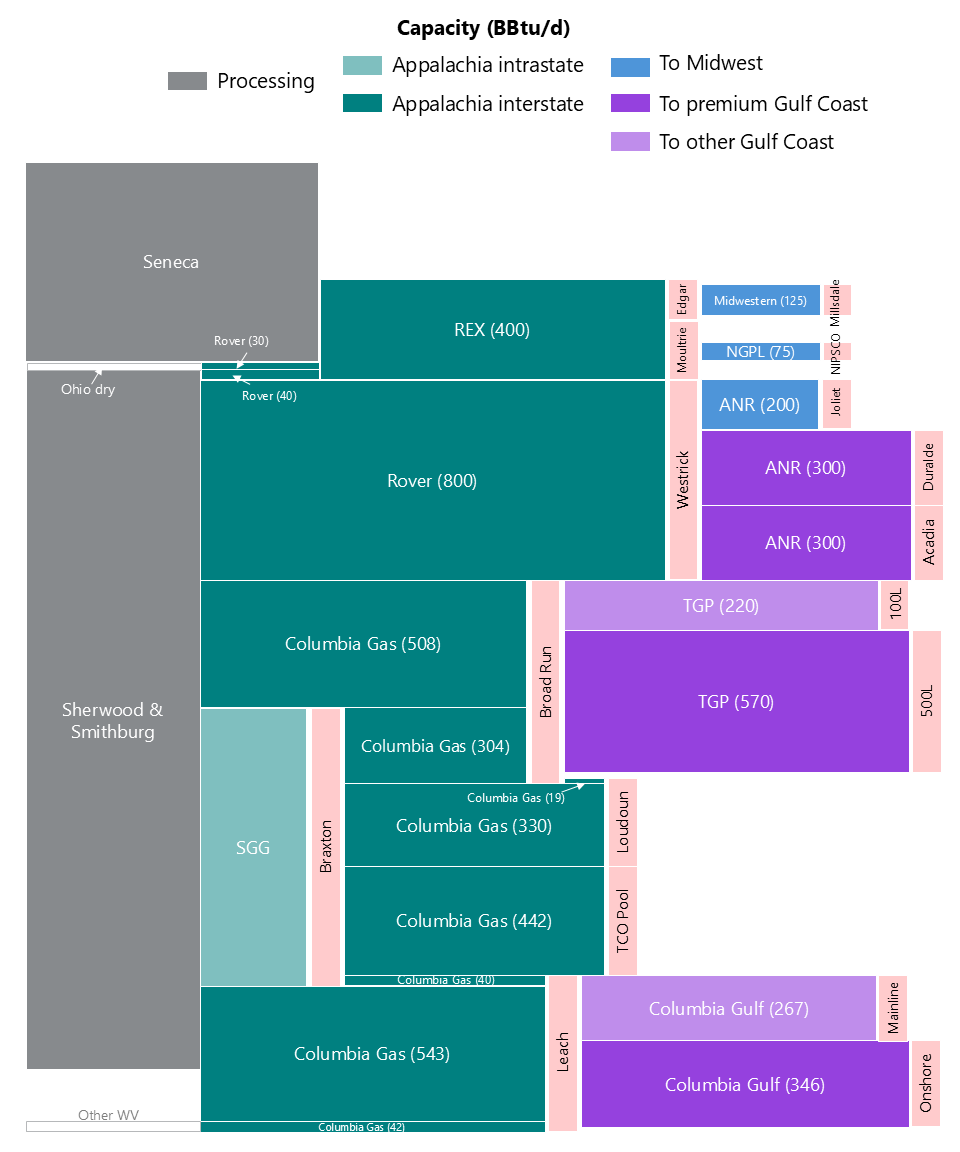

Ohio production fills less than half its 400 BBtu/d of REX capacity

In West Virginia, Antero has more in-the-money FT than processing capacity

The Ohio sale to Infinity solves the first problem, and the HG acquisition addresses the second.

Figure 1 | Antero’s firm transmission capacity (to scale)

Recently, other Appalachian operators have consolidated aggressively, while Antero and Range sat out. Now, Range guides to 20% organic growth by 2027. With scale growing increasingly important in a likely-persistently-constrained basin, Antero’s future as an independent company depends on its ability to scale up.

While it has the most extensive4 and best-structured transportation portfolio of any major Appalachian operator, its access to processing capacity has limited the company's growth potential for its core rich-gas West Virginia asset. With 13 trains at Sherwood and 1 at Smithburg, the company accesses 2.8 Bcfd of processing capacity, versus 3 TBtu/d of capacity to move gas away from Sherwood/Smithburg.5

But buying HG was not the only way Antero could have addressed this. Most straightforwardly, the company could have backstopped another Smithburg train, which was previously permitted, and indeed Antero paid $12 million in 2022 to cancel its construction. But the company dismissed this possibility on its 1Q25 earnings call:

If you have to make future commitments on FT or processing, that’s not something we’re interested in. … [We] are full or above nameplate on the processing.

This reticence points to a broader shift toward dry-gas growth, which does not require long-dated midstream commitments, especially as Northeast demand grows.

Another alternative would have been for Antero to ramp up its own West Virginia dry-gas production, bypassing the Sherwood/Smithburg constraint and connecting volumes directly into Stonewall Gas Gathering. Instead, the company expects to integrate HG’s production into SGG, choosing to buy dry-gas volumes rather than drill its own, either because HG’s PUDs are higher-quality or because a PDP-PUD valuation gap made the acquisition more capital efficient.

Future of Ohio gas production

Following Marcellus takeaway challenges, Utica operators contracted more aggressively. The play’s subsequent underperformance left some takeaway capacity available and only the pure-plays driving Ohio activity.

Infinity intends to ramp up activity on the newly acquired asset, which highlights a broader development trend in today’s capital-disciplined environment. Investors in mid- and large-cap independent E&Ps have little appetite for exploration risk, instead focusing on capital efficiency. HG derisked its position to the extent that Antero could take it on. In contrast, the next development phase on the Utica asset is now too risky to compete in Antero’s portfolio.

But gas demand growth is accelerating, and long-dated Henry Hub prices are likely to rise, creating opportunity for the small-cap or PE-backed E&Ps now proving up a next round of dry gas acreage. With Haynesville productivity deteriorating even more sharply than in the Utica and weak oil prices slowing associated gas production growth, the opportunity for Ohio growth — which is better-connected to markets than the rest of Appalachia — is improving. Infinity’s presentation indicated that it acquired REX capacity6 as part of the deal. In a rising Henry Hub price environment, this capacity becomes more valuable.

Outside of the companies party to the deal, MPLX is the biggest winner. While Antero’s processing commitments likely reduce MPLX’s near-term revenue exposure to Antero’s declining Seneca throughput, the prospects for future throughput at MPLX’s Seneca plant are much stronger with a new buyer that intends to invest in the asset. Tallgrass also stands to benefit, as Antero’s REX contract expires in early 2035 and, prior to that, steps down from 400 to 200 BBtu/d for its last five years. The odds of this capacity being renewed increase with a resurgence in Ohio activity.

Taken together, the HG acquisition and Ohio divestiture reframe Antero’s competitive position. In a basin where capital discipline now means avoiding new off-balance-sheet midstream commitments, large operators’ growth will come from underutilized processing or flexible dry-gas acreage. For Antero, the choice was clear: rather than fund a more speculative Utica development phase or backstop another Smithburg train, it bought dry-gas volumes that fit its existing midstream footprint. For Ohio’s pure-plays, though, the opportunity remains. Henry Hub prices are rising, and a more favorable takeaway position relative to the Marcellus means the Utica may enter another gas growth phase.

Both Antero Resources and Antero Midstream

In a joint venture with Northern Oil and Gas, which takes non-operated positions

Not by me! I told easily 20 different hedge funds in 2020 that the NYMEX strip would reprice before Antero faced a liquidity crisis, and that the FT, which many investors myopically thought would always be a millstone, would turn into a valuable asset. Less impressively, I didn’t quit my job to put the trade on myself.

Relative to its production

Typically, processing capacities are quoted for inlet volumes rather than residue, meaning the effective residue capacity would be ~2.5 Bcfd. However, for 1,100 Btu gas, which is what has been flowing from Rover onto Sherwood, 2.5 Bcfd could correspond to 2.8 TBtu/d. With Antero’s TCO Pool and Leach deliveries impossible to isolate from other operators’, we can’t say definitively how short the company is on processing capacity relative to takeaway capacity. However, we know it to be at least 40 BBtu/d, which has been the company’s shortfall this week relative to its Broad Run capacity on TGP. Realistically, I expect the true figure to be in the 100-200 BBtu/d range.

I reached out to both companies’ IR teams, but haven’t heard back yet, as to whether Infinity will assume all of Antero’s REX capacity, and whether the deal also includes the downstream capacity on Midwestern and NGPL. My guess is that Antero’s REX, NGPL, and Midwestern capacity were all included. Demand charges on the three tranches total ~$75 million annually, although the spreads between receipt and delivery prices cover most of this.

Thank you for the article. Do you see this setting off more M&A activity in the Appalachia basin? If so, what companies do you think will be involved and benefit?

This article is brilliant. An abject lesson in how much I have yet to learn.