The CC backlog is bullish for gas demand

What the growth since 2019 tells us about the next five years

Capacity auctions signal the need to add baseload power plants, but turbine manufacturers, after the lost decade of the 2010s, lack the capacity to build them. The CC shortage is no longer just an industry headline; now it’s making the Wall Street Journal and Financial Times. For the gas market, the question is whether this backlog will constrain data center growth and, by extension, gas demand.

Recent experience suggests that’s the wrong frame, because utilization and heat rates are as important to gas demand growth as nameplate capacity additions. Since 2019, combined US nuclear, coal, and combined-cycle capacity declined each year, even as load growth accelerated. And the existing fleet still has room to run.

Decomposing recent gas demand growth

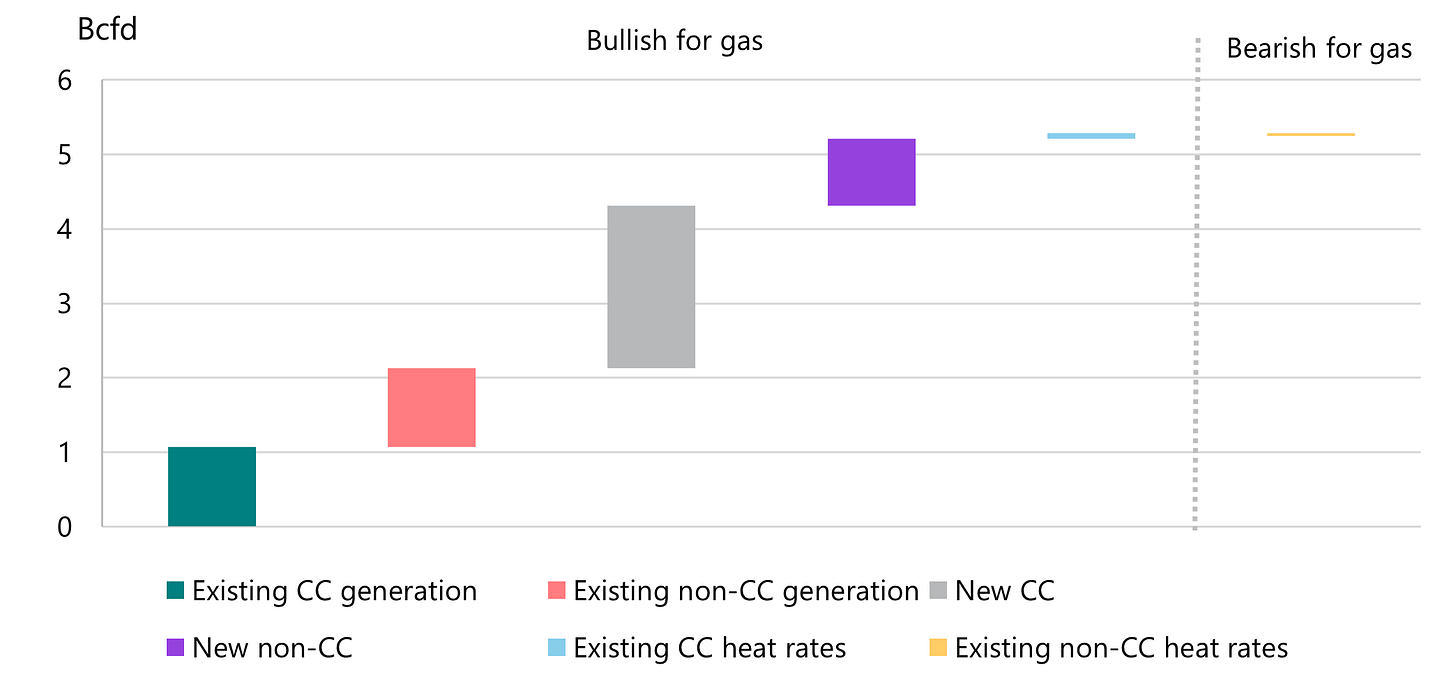

Since 2019, the data is clear: capacity additions don’t tell the whole story. At the Lower-48 level, changes in utilization of existing capacity accounted for more than 40% of gas demand growth over this period. Along with changes in generation, the changing mix of which plants ran, and for how long, affected the aggregate system heat rate across existing capacity.

Interestingly, system-wide heat rates rose slightly for existing CCs but declined modestly for other gas capacity. The likely implication, then, is that the coal retirements changed which gas units were marginal: that a cycling CC replaced loads previously served by a since-retired coal plant and a gas peaker. Rising heat rates are likely to be an even bigger driver of gas demand going forward, given a slowing pace of CC additions alongside continued coal retirements and load growth. Monitoring only the change in gas generation understates the Btu impact that is most relevant to the gas industry.

Figure 1 | Decomposition of US gas demand growth since 20191

In other words, the dearth of CC capacity under construction need not limit growth in gas demand. More generally, forecasting gas-fired generation growth based on gas capacity additions is likely to overstate demand in some regions and understate it in others. Cheniere laments LNG tourists, but power tourists are outing themselves by building generation outlooks based on capacity additions.

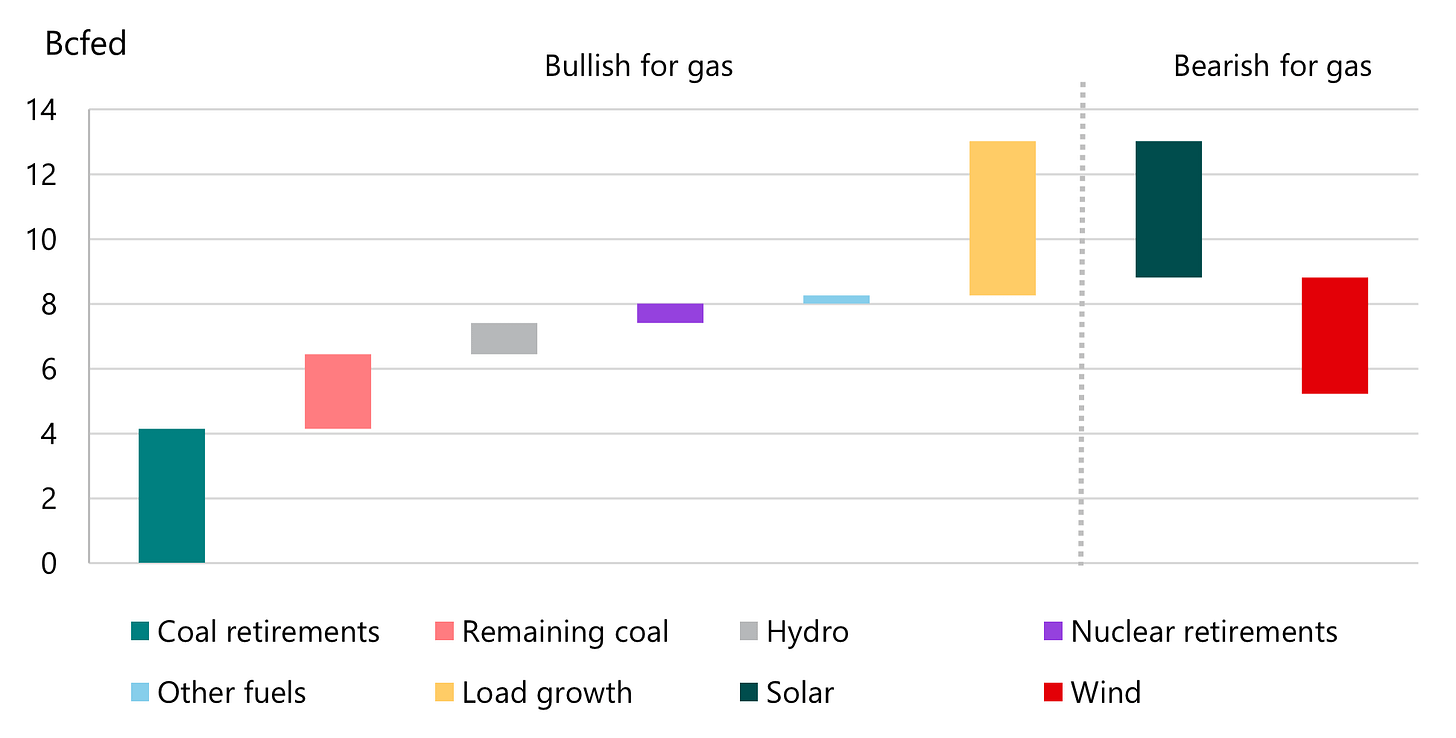

What were the drivers of gas demand growth?

In the last five years, ~50 GW of coal capacity retired, and these plants generated ~4.1 Bcfed in 2019. Load growth added ~4.8 Bcfed of gas demand over the same period, weighted to the last few years. However, increases in wind and solar capacity added ~7.8 Bcfed of zero-marginal-cost generation, partly offset by nuclear retirements and reduced hydro utilization.

Most surprising, however, is that coal generation at the remaining plants declined by ~2.3 Bcfed over the same period. In an environment of rising loads and higher gas prices, a naive model would predict rising utilization of the remaining coal fleet.

Figure 2 | Drivers of gas demand growth since 2019

But the aggregate numbers mask significant regional variation. Disaggregating these trends helps address why gas also gained at the expense of remaining coal capacity.

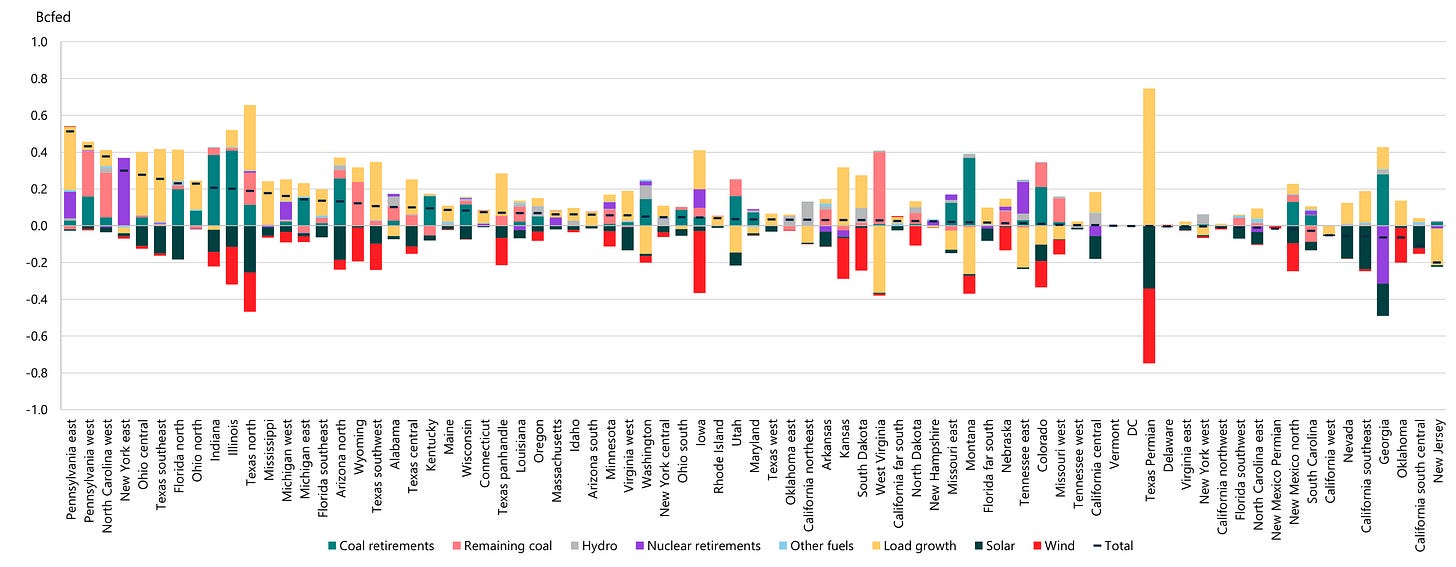

Insights from regional variation

Some states, such as Kentucky and South Carolina, showed the expected pattern: coal retirements (teal bars in Figure 3) as a bullish driver for gas demand, partly offset by increased generation at remaining coal facilities (pink bars). In other states, such as Colorado and New Mexico, growth in wind and solar generation (navy and red bars) more than offset declines from coal retirements, putting additional pressure on the remaining coal capacity. These divergent patterns highlight how regional renewable buildout will affect gas demand as much as coal retirement schedules.

Figure 3 | Regional drivers of gas demand growth since 2019

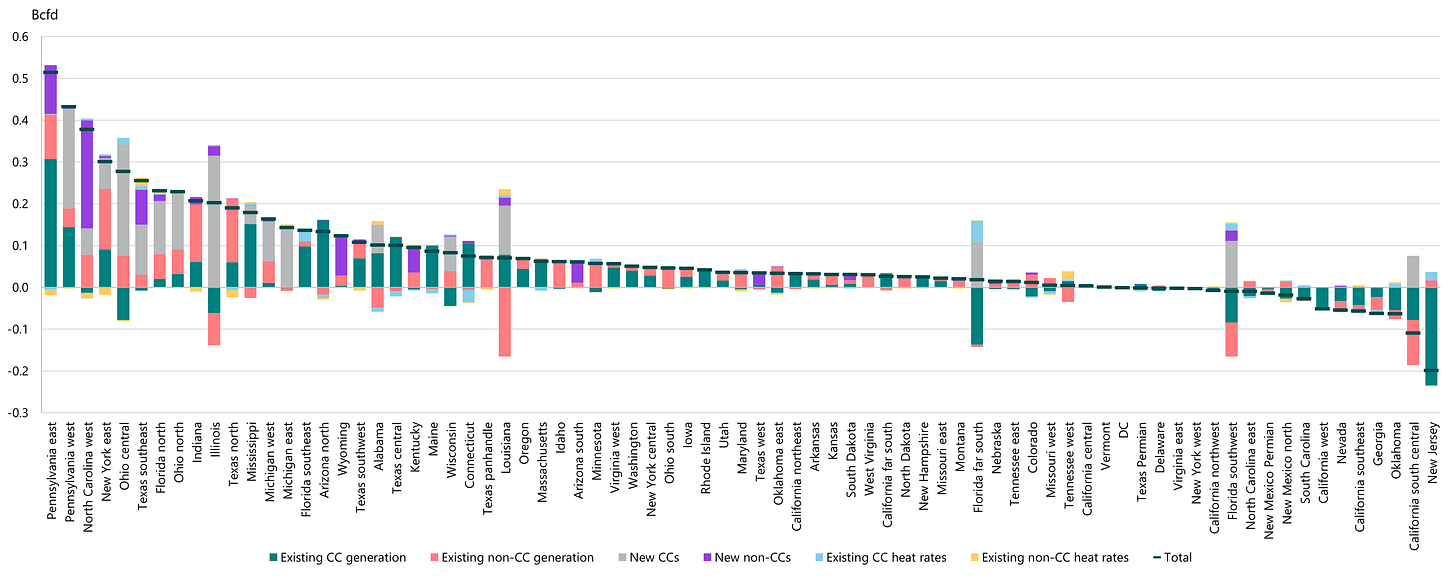

In the four regions where generation at existing coal plants declined the most, new gas capacity was the proximate driver. New combined-cycle capacity (gray bars in Figure 4) in western Pennsylvania and Ohio displaced coal in West Virginia and western Pennsylvania, while in North Carolina, Duke converted existing coal capacity to gas, and PacifiCorp did the same at two of its Jim Bridger units in Wyoming. In other regions, gas demand upside — whether driven by coal retirements or by load growth — was mostly realized via higher generation at existing CCs (teal bars).

Figure 4 | Decomposition of regional gas demand growth since 2019

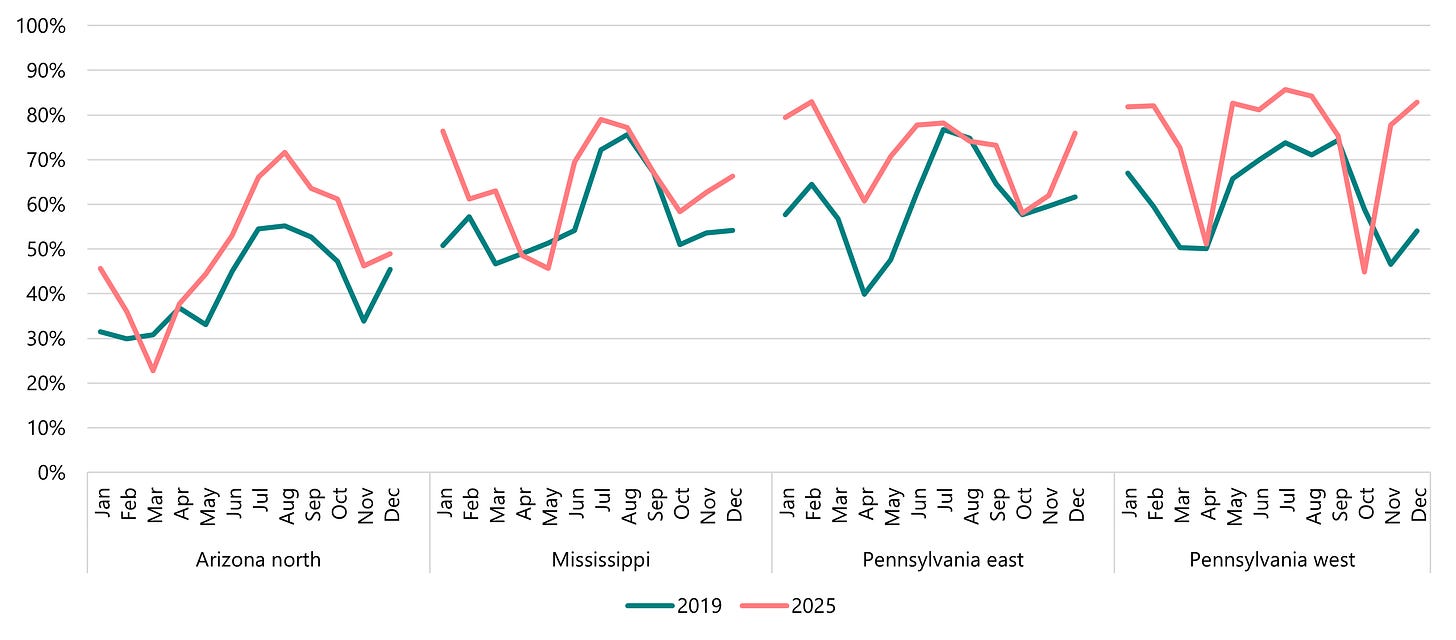

In each of northern Arizona, Mississippi, and both eastern and western Pennsylvania, higher utilization of existing CCs added more than 140 MMcfd of demand, as CC capacity factors rose by 8-13 percentage points.

Figure 5 | Combined-cycle capacity factors in key regions

Why this pattern will persist

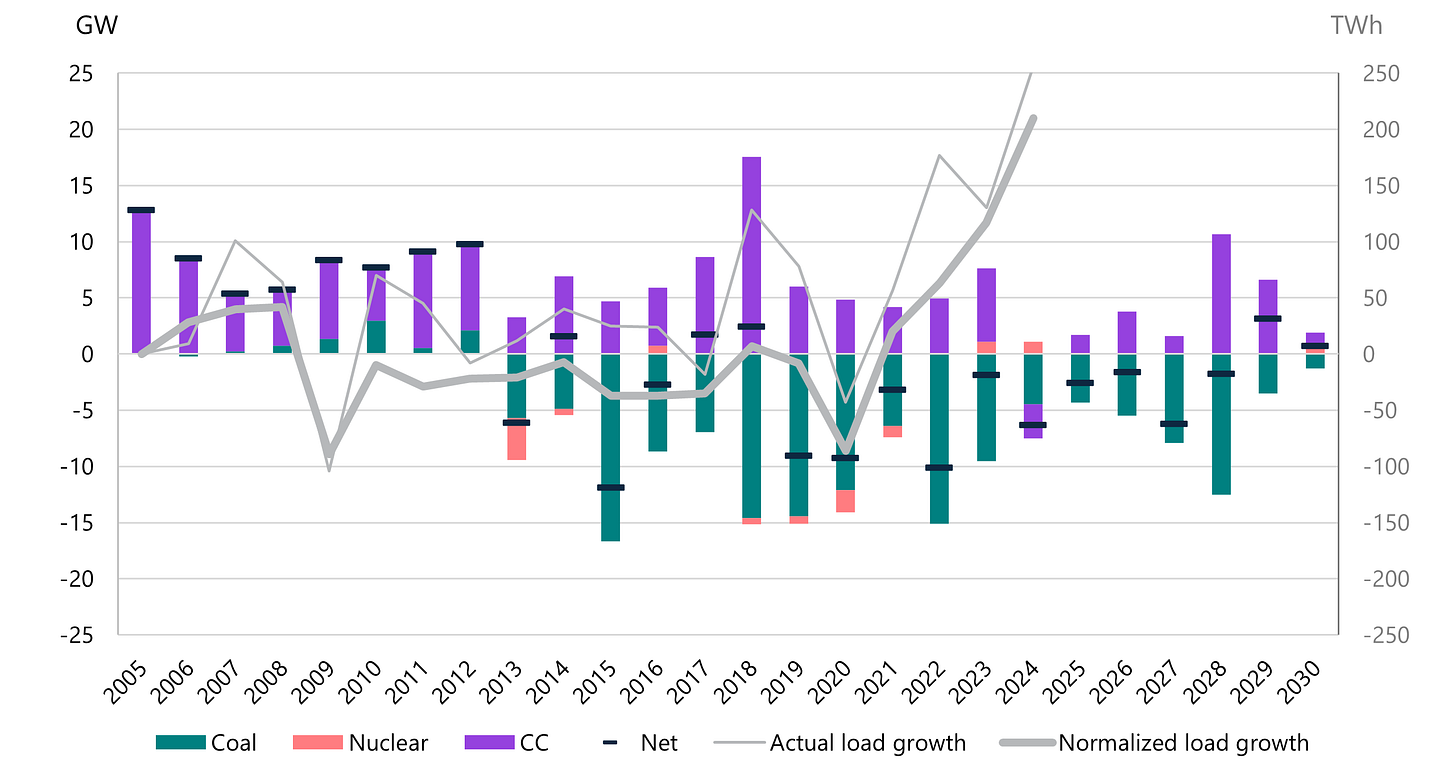

The conditions that drove gas demand growth since 2019 aren’t going away. Since 2012, total US nuclear, coal, and combined-cycle capacity declined ~60 GW, to ~600 GW currently. Wind and solar additions2 offset about a third of that decline, but the equally important factor was the flattening of electricity demand. Weather-normalized US loads actually declined between 2011 and 2017, driven by a weak economy and efficiency gains. Growth resumed in 2018-19, paused during the pandemic, and has since accelerated sharply, returning to the ~60 TWh annual pace last seen in the early 2000s.

And with lead times for new CCs stretching to five years, nuclear even longer, and no new coal planned, the trend of declining baseload capacity will continue into the medium term.

Figure 6 | Annual baseload capacity additions and cumulative load growth from 2019

The continuation of that capacity trend, alongside increasing loads, indicates that the period since 2019 is a useful guide to how gas-fired generation is likely to evolve over the next five years.3

What this means for the next five years

The next five years are less about new steel and more about sweating the existing fleet.

Coal retirements and strong load growth are both likely to persist, although the former carries more risk. Under Trump, the Department of Energy ordered several coal units to remain open. And previously, Southern, Duke, Dominion, Alliant, Vistra, and Xcel delayed previously scheduled retirements, primarily due to stronger load growth. But some coal retirements will still proceed, resulting in higher capacity factors at both remaining coal and existing gas units. This will translate to gas demand growth, both directly via higher generation and indirectly through rising system heat rates.

Which of these factors dominates will vary regionally. In Arizona, the existing CC fleet can absorb continued load growth and/or retirements. In western Pennsylvania, a rising call on gas will likely manifest primarily in higher system heat rates, as less-efficient capacity must be dispatched. In the next post, I’ll examine planned retirements, their prospects, and the likely impacts on coal and gas capacity factors.

Throughout, I analyze the latest available data, 4Q24 through 3Q25, compared with 2019. Occasionally, I use the shorthand “2025” to refer to the former period.

Derated at 10% of their nameplate capacity

On power, I’m operating more with heuristics than with asset-level detailed modeling, but the availability of data means it’s possible to translate these heuristics into granular market insight, even in the absence of an hourly dispatch model

Thank you for the detailed article. It was very informative. What utilization rate can a typical CC plant achieve with normal maintenance downtime? In Figure 5, it looks like the four regions peaked at about 70-85% utilization rate. Does this indicate that the existing CC plants have another 5-10% utilization available in future on top of the 8-13% increase for the past five years?