How I think about being an analyst

Models, heuristics, and conviction — and why I'm skeptical of gas production scrapes

This methodological reference piece addresses how I approach analysis and uncertainty. Measured Depth will pause until January 6, but I expect to refer back to this framework in future posts.

About 10 years ago, I gave a presentation to a large utility’s board, and afterward, one of the directors asked me if I had been doing this for a long time. Thinking about his question crystallized something for me — that I’ve always been an analyst. In kindergarten, I checked the Rangers and Mavericks box scores and standings in the Dallas Morning News every morning.

I’m writing this because methodology matters, especially when markets are noisy and data are incomplete.

Conviction and uncertainty

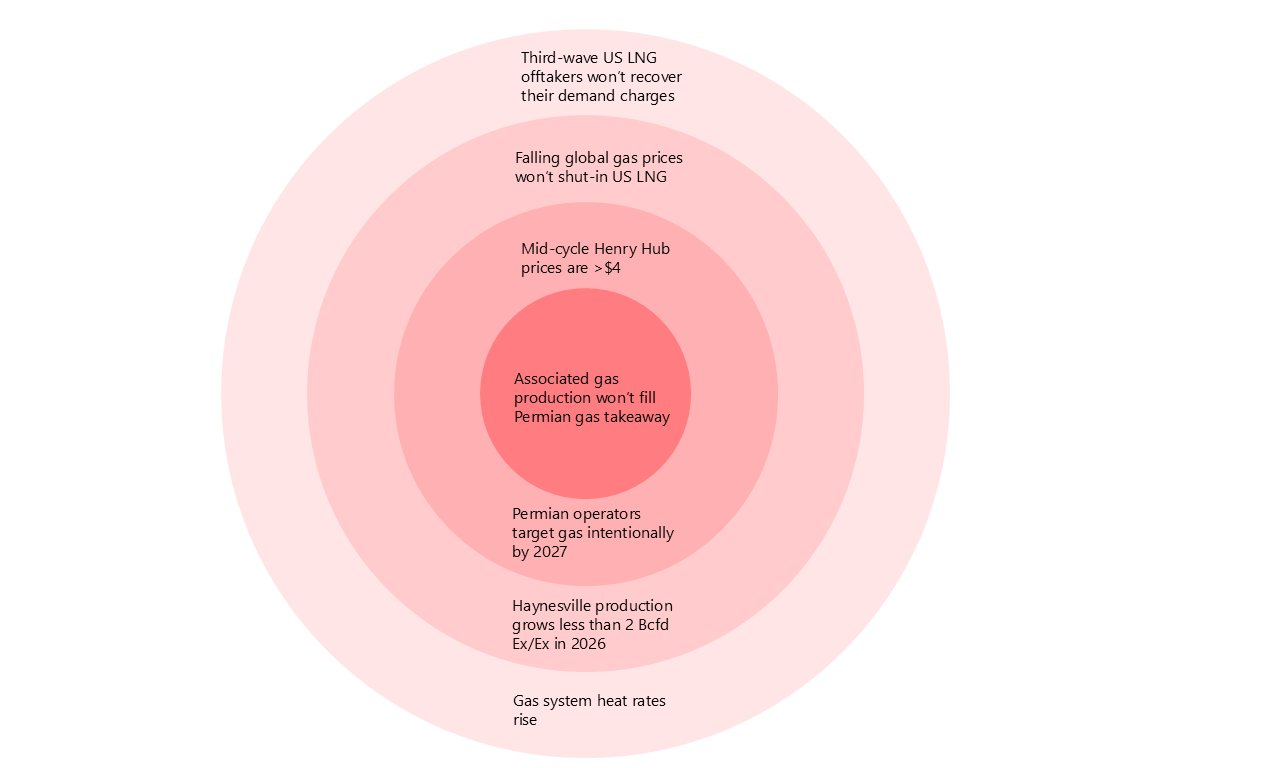

Although I’ve been an analyst for a long time, a book I read this summer about religion, of all things, helped me articulate how I approach my work as an analyst. In The Road to Wisdom, Francis Collins writes about a web of beliefs, wherein the believer is most sure of (and attached to) the views at the center, but less so to ones further out.

And this resonated with me because I think the core job of being an analyst is deciding when to change your mind: thinking not just about models but about heuristics and how well-suited your tools are to capture changing market dynamics, about where models might not be accurate even though they’re precise, and updating your priors accordingly. Do it too infrequently, and the market passes you by; do it too often, and no one will take you seriously. It’s essential to be transparent not just about your analysis but about how strongly you hold it, which requires both methodological rigor and epistemic humility.

Figure 1 | Views about the gas market

Heuristics versus models

Some analysts — typically older and oil-focused — eschew models, arguing that the job is about more than pressing run and that understanding how companies (and sometimes countries) make decisions matters more. It probably goes without saying that I do not belong to this school. I’m an unabashed model lover, not because they are magic, but because they are tools for rationalizing how disparate pieces fit together, in ways that aren’t obvious when looking at problems in isolation. But I nonetheless think the OPEC-watcher’s critique has some merit.

The most important thing about models is to understand what’s not in them. In the 2010s, our Henry Hub forecasts were wrong because they didn’t account for future breakeven improvements. More broadly, you need to consistently ask yourself not just whether the model’s input data are robust but whether the model’s algorithm needs to change to accommodate new features of the market.

For example, Permian gas pipeline development is accelerating and is likely to outpace the growth in associated gas production. That, in turn, will narrow basis differentials. But what would those narrower basis differentials, in conjunction with higher Henry Hub prices, mean for upstream activity and therefore the pace of production growth? Before you can consider using a model, you need to have a heuristic.

At Wood Mackenzie, I spent 10 years using one linear programming model to forecast North American gas flows and basis differentials; another to forecast global LNG development, flows, and prices; and others to optimize power systems. Next, I went to RS Energy Group, where we had a best-in-class understanding of onshore North America upstream but no long-term activity model, to say nothing of a gas pipeline flow model. While I prefer having those tools, a strong mental model is more important. Because at the end of the day, having a model isn’t about updating the numbers and pressing run — it’s about understanding what the model does and what it doesn’t, and how to rework it as the market changes.

In practice, I can tell you where specific compressor stations are on Transco and TGP, but I can’t rattle off all the regas terminals in Japan. So when I write about sustainable long-term global gas prices, or clearing the medium-term LNG oversupply, I’m using a heuristic rather than detailed dispatch or flow models.

Accuracy versus precision

Sometimes, though, the problem isn’t the heuristic but the availability of data. My econometrics professor told the joke about the econometrician looking for a lost ring under the lamppost, not because that’s where he lost it, but because that’s where the light was. And I think of this often with respect to models of gas production scrapes, whose problems are twofold:

First, the independent variable is itself unknown: operators report well-level two-stream production to state regulatory agencies, but they do not report three-stream volumes. The EIA reports dry gas production only at the state level, and even then with a three-month lag. In the Permian, wellhead NGL content and ethane extraction both vary widely, meaning no one really knows what gas production was, even historically.

Second, the relationship between observed and unobserved gas production changes frequently. With scheduled quantity data reported for interstate gas pipelines, you can observe how much production moves onto interstates in real-time. But modeling total gas production from the volume moving onto interstates requires that relationship to be stable, which it is not.

Recently, the in-service of Louisiana Energy Gateway re-routed flows from less-visible intrastates.1 Applying the same gross-up factor resulted in Haynesville production being substantially overstated until analysts recalibrated their models. But even that recalibration doesn’t solve the problem, because you don’t have any way of knowing how much gas was redirected versus newly turned in line. You can make an assumption, but it’s that view that’s driving the model results, not the observable data.

If growth were mostly coming from Appalachia or the Rockies, production scrapes would probably have more signal value than noise. But growth is overwhelmingly coming from the Haynesville and the Permian, where intrastates move a large and growing share of production, and NGLs make historical dry-gas production estimates uncertain. With infrastructure as large as LEG, these model deficiencies are obvious. But gas flows change not only with new pipelines like LEG but also with new gathering interconnects, processing outages, or shifts in destination prices.

So when someone asks me to explain why gas production has unexpectedly risen or fallen, my answer is often to question whether it has indeed.

How I reevaluate when evidence changes

I make a good conference panelist because I’m opinionated2 and not afraid to express views outside the consensus. With this framework, I tend to grow less certain before eventually changing my mind. This year, though, I doubted CP2 FID until the moment it happened:

First, I weighed soft factors — like the ongoing lawsuits and arbitration between Venture Global and its Calcasieu Pass offtakers — too heavily relative to cold hard dollars: Venture Global offered the lowest capacity charges.

Second, I held too much conviction relative to how connected I was with LNG developers and offtakers. SPAs are public, but tracking those agreements isn’t enough to call which projects will proceed. Pointing out that some of CP2’s SPAs might have lapsed was appropriate; extending that to FID risk was not.

For me, good analysis is less about never being wrong than about knowing when to become less certain. With that in mind, don’t hesitate to comment or e-mail when your analysis suggests I should be changing mine. And in the meantime, merry Christmas!

Of course, LEG is also an intrastate, but it’s one without much intrastate demand, meaning its flows are mostly synonymous with its deliveries into interstates near Gillis.

My mom used to tell a story of how, after I went to college, dinner conversation suddenly got so…peaceful.

I would love to read your additional thoughts on some of your “pretty certain” beliefs shown in the outer circles in Figure 1. I think your opinion on why they may or may not be true, and the impact on different players in the value chain would be very interesting reading. For example, Permian operators targeting gas production and what that means for gas, liquids, and oil prices? Or your listing of gas system heat rates increase. How would that impact natural gas producers or pipelines, if at all?

Love the mom anecdote!