Why the stakes in US LNG are so high

The economics behind the accelerating pace of FIDs

I cannot recall another time in my career when I’ve seen such a fissure between how companies with similar portfolios see the market.

At the beginning of this year, North American LNG export capacity totaled about 13 Bcfd, with an additional 13 Bcfd under construction at Corpus Christi, Plaquemines, LNG Canada, Golden Pass, Costa Azul, Port Arthur, Cedar LNG, Woodfibre, and Rio Grande. But the outlook for pre-FID projects was challenging if not outright dim: Henry Hub prices were climbing, TTF prices were falling, and EPC costs were rising. Every consultant was talking about an oversupplied LNG market later this decade and into the early 2030s.

So, naturally, five additional projects, totaling 8 Bcfd of capacity, took FID.1

This surge in FIDs has come with a different mix of developers, project structures, and offtakers relative to prior waves of North American LNG development. Shell is the largest US LNG offtaker, but the company has not signed any US LNG SPAs since 2022, and its CEO called some recent FIDs “not economically fully rational.” Similarly, Cheniere is the largest US LNG developer, accounting for 41% of onstream capacity, but the company sanctioned only 5% of US capacity that took FID this year.

The recent earnings season highlights a growing divide between companies that are investing aggressively in US LNG, expecting it to remain highly profitable as the LNG market grows, and those taking a more conservative approach, even sounding alarms about oversupply and the potential for new US LNG investments to end up underwater.

Understanding US LNG economics

In its earnings presentation, NextDecade highlighted that spot LNG from Rio Grande would have been worth $7.20/MMBtu over the last 15 years, had the facility been online. And no question: US LNG investments have been extremely profitable over their first decade.2 But the forward curves are narrowing, and more importantly, are misleading about the profitability of investing in new liquefaction capacity.

For oil, building enough export capacity to close regional price differentials requires a relatively small infrastructure investment. Enterprise’s proposed 2 Mbd Sea Port Oil Terminal, after cost overruns, is expected to cost ~$3 billion. With a typical capital structure, that probably translates to ~$0.50/bbl for customers.

Gas is different. An LNG facility requires not just land and berths but the full cryogenic infrastructure to supercool gas into a liquid. Modern construction costs for US LNG facilities typically run ~$15 billion for a ~2 Bcfd project — five times the capital to move one-sixth of the volume. For offtakers, that translates into capacity charges in the $2.50-3.00/MMBtu range, equivalent to $15-18/bbl.

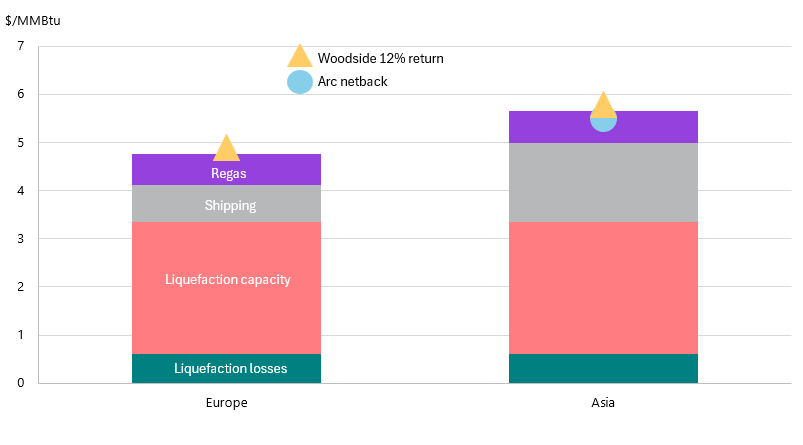

Add on the cost of gas used in liquefaction, shipping costs,3 and regasifcation, and you need to believe in a US-Europe price spread of at least $4-5/MMBtu — and a US-Asia spread of at least $5-6/MMBtu — to make money on US LNG capacity in the long run. Recent earnings commentary substantiates these ranges: Arc Resources receives a netback price of JKM less $5.50/MMBtu and Woodside referenced a required spread of $4.90/MMBtu to Europe and $5.80/MMBtu to Asia to achieve a 12% return.

Figure 1 | US LNG long-run marginal costs

Fundamentally, the company taking the spread risk between Henry Hub and global prices is betting that spreads will be sustained above $4/MMBtu, or that it can eventually transfer that risk to another party. Sometimes the risk-taker is the LNG developer — such as with unsold capacity — but more commonly it is the LNG offtaker. In cases like Sempra’s Port Arthur Phase 2 or Woodside’s Louisiana LNG, those lines are blurred.

What determines who wins those stakes

The ultimate profitability of these US LNG investments, then, depends on three4 key levers:

The degree and longevity of medium-term LNG oversupply

Long-run LNG demand growth and TTF/JKM prices

Long-run Henry Hub prices

On the last point, it’s hard to tell to what extent US LNG offtakers are meaningfully more bearish than I am on Henry Hub, or whether they think US LNG investments will pay off even as Henry rises. The first two levers I’ll address in later installments of this series.

Why this creates divergence in company behavior

These long-run economics are precisely what companies are reacting to.

LNG developers and offtakers aren’t just betting on next winter or the next commissioning cycle — they’re locking themselves into multi-decade exposure to the spread between Henry Hub and global prices. And neither the long-dated Henry Hub nor especially the JKM or TTF markets are liquid enough to hedge that risk directly.

So companies must form their own views on questions like gas’s competitive position relative to coal and renewables, whether LNG projects under construction will be completed on time, and even macroeconomic growth. As a result, companies with broadly similar portfolios are coming to very different conclusions about the next decade. Some see long-run spreads easily clearing the $4–6/MMBtu hurdle implied by today’s LNG cost structure and are investing accordingly. Others are moving cautiously, taking exposure only when it strengthens a core midstream or upstream position. And a third group is avoiding direct LNG exposure altogether.

How that divergence shows up across E&Ps, LNG developers, and portfolio players is the subject of the next post in this series, followed by ones on the medium-term oversupply and the long-term outlook for LNG demand and prices.

Subscribe at www.measureddepth.com to make sure that you receive the rest of this series on US LNG.

No others are imminent, but it wouldn’t shock me to see Commonwealth LNG take FID sometime in the first half of next year

The tenth anniversary of Sabine Pass Train 1's substantial completion is approaching, in May 2026

Also more expensive than oil because the ships need to keep the LNG cold

EPC costs can be a fourth, although some projects mitigate this with lump-sum turnkey contracts, wherein the EPC contractor bears the risk of overruns