Now is the wrong time to be contracting for US LNG

The global market can't support prices high enough to deliver returns

I’m more optimistic than most on medium-term US LNG export volumes, as price-sensitive demand typically emerges as LNG prices fall into the $6-8/MMBtu range. I’m far less sanguine about the long-run profitability of third-wave US LNG investments. That skepticism reflects both higher expected Henry Hub prices and a market that is misreading cyclically high LNG prices as structurally sustainable.

At its core, US LNG is a bet that the long-term spread between US and global prices will remain wide — at least $5/MMBtu to Europe or $6/MMBtu to Asia. With a growing consensus that mid-cycle Henry Hub prices have now shifted to the $3.50-5.00/MMBtu range, that implies sustained global LNG prices of at least $10/MMBtu — a level that history suggests is difficult to maintain.

This post focuses on price sustainability and returns; the next will examine who is backstopping new US LNG projects — and why.

What LNG price is sustainable?

Only two extraordinary dislocations kept global gas prices this high on average over the last 15 years: the post-Fukushima nuclear shutdowns beginning in 2011, and the loss of Russian pipeline gas to Europe after Russia invaded Ukraine. These two events tightened the market by ~6 Bcfed and ~10 Bcfd, respectively.

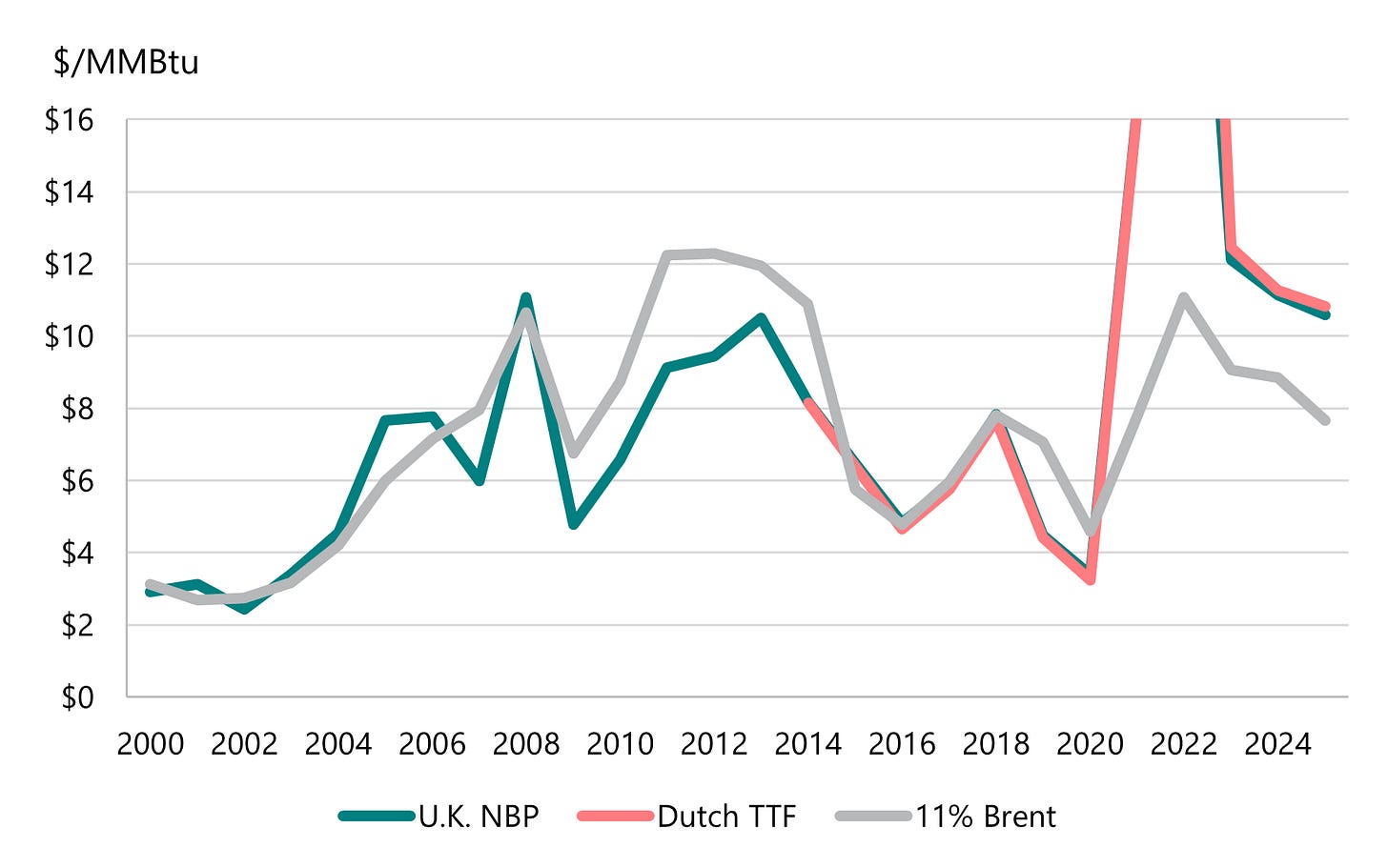

Because LNG projects take 3-5 years to develop, these shocks produced extended periods of elevated prices. But that persistence reflects project cycle times, not a new equilibrium. In the 10 years pre-Fukushima, European gas prices averaged ~$5.50/MMBtu, and Brent-indexed LNG contracts priced at similar levels. Even excluding the low prices in 2020 during the pandemic, European gas prices averaged just ~$7.75/MMBtu in the 2014-21 interregnum between the two shocks.

Taken together, the evidence points to sustainable LNG prices in the $6-10/MMBtu range. An $8 mid-cycle LNG price is ~$2/MMBtu below the levels needed to justify new US LNG investment in a higher Henry Hub price environment.

Figure 1 | European gas prices and oil-indexed LNG prices

Western Europe offers a useful stress test. Despite being among the richest regions in the world, persistently high electricity prices are proving economically damaging and politically destabilizing. Whether driven by decarbonization policy, imported fuel costs, or temporary shocks, elevated power prices are not politically sustainable — even in advanced economies.

Why is $70 oil sustainable but $12 gas isn’t?

The Ukraine crisis disrupted multiple commodity markets, but gas more so than others. Oil and other commodities are flexible, moving by ship and truck and easily rerouted to avoid sanctions. Piped gas, by definition, has a fixed destination.

That flexibility makes $70 oil politically and economically tolerable in a way that an energy-equivalent $12 LNG price is not. Oil’s delivered cost is only modestly higher than its benchmark price, whereas even in the US, delivered gas costs are typically more than twice as high as the Henry Hub price.

Gas’s core challenge is infrastructure intensity. Unlike oil or coal, LNG requires large, capital-intensive assets across the value chain. Even in power generation — the most viable end-use for LNG — gas must compete not just on fuel cost, but on the cost of building and integrating this infrastructure relative to alternatives like coal and solar.

Gas remains widely used for space heating in North America and Europe largely because this infrastructure was built when gas was cheap. Where new gas infrastructure is required, developers typically opt for electric heat.

How competitive is gas in power generation?

So the future of strong LNG growth globally is predicated on power generation, where consumption is more discrete and therefore infrastructure requirements less extensive. And the US LNG bulls typically point to gas’s potential to both reduce emissions and serve growing economies globally as reasons for optimism. But even delivering gas to power plants requires major infrastructure investment relative to other options like coal, which can be shipped by rail, or solar. For LNG demand to grow strongly, LNG prices need to be competitive, accounting for the cost of downstream infrastructure development, with coal and solar.

With ~550 Bcfed of thermal coal burned globally, gas’s displacement potential in power generation is enormous. But the US experience is illustrative. From 2008-24, gas displaced ~20 Bcfd of coal in power generation, but this demand did not support attractive margins for E&Ps. So far this year, E&Ps’ returns have been much better, because consumers with higher-value uses for the gas have outbid price-sensitive domestic power generators. As a result, gas has lost ~2 Bcfd of market share to coal in power generation.

In other words, a well drilled in the 2010s to displace coal in US power generation produced gas you could sell, but it was a well you would’ve rather not drilled. Similarly, Gulf Coast LNG lifted at $4.60/MMBtu FOB (equivalent to 115% of $4 Henry Hub) can displace coal globally, but it’s LNG you would have rather not contracted for.

For US LNG offtakers, global LNG demand growth is not enough — they need that strong growth at high prices. And that’s where recent offtakers seem overconfident. In the final post of this series, we’ll examine who is still underpinning new US LNG projects and why.