The end of the coal retirements tailwind

Why winter reliability is reshaping the coal-to-gas outlook

Coal retirements drove 4.1 Bcfd of gas demand growth since 2019, and gas gained an additional 2.3 Bcfd of market share by displacing coal at the remaining units. But with rising gas prices, coal displacement reversed in 2025 and is poised to do so again this year, as LNG exports ramp up. In this higher gas price environment, coal retirements, then, will be the most important driver of gas’s share of fossil generation.

However, the pace of retirements is slowing. The key reason is not political, nor primarily economic; rather, coal retirements have become a reliability concern. Whether a plant can retire now depends less on its average utilization or margin and more on whether the system can replace its output through the winter — when gas generators compete with LDCs and LNG for both volume and deliverability.

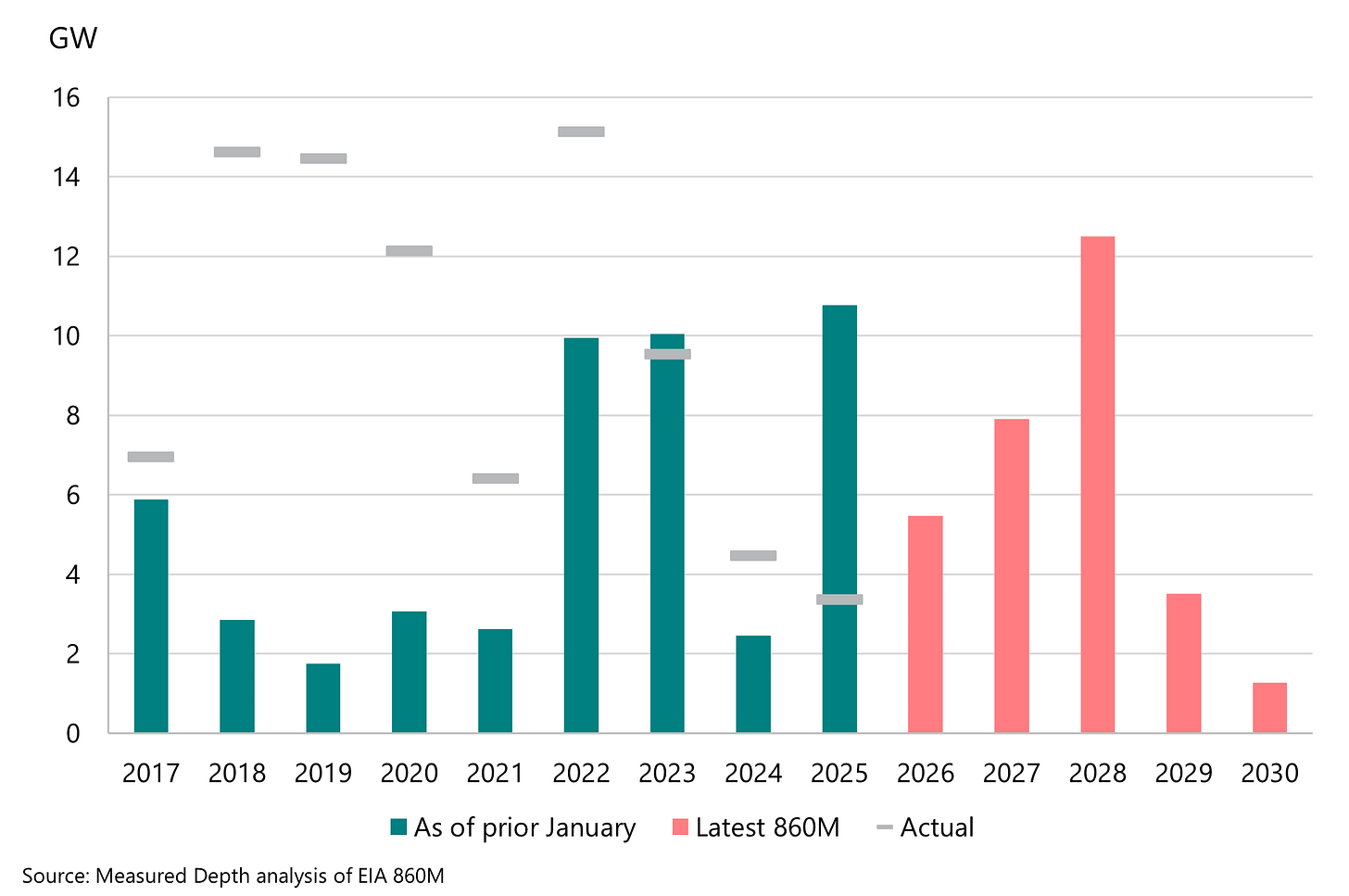

Last year, 3.4 GW of coal capacity retired, the lowest figure since 2011. From 2018-22, coal retirements (gray lines in Figure 1) consistently outpaced utilities’ plans from the prior year, shown in the teal bars. Then, the combination of low gas prices and an accelerating buildout of wind and solar capacity put pressure on power prices, coal capacity factors, and coal generators’ margins.

Now, though, the market has changed in several important ways. Both electric load growth and LNG exports are accelerating, while deteriorating well performance in key plays also pushes Henry Hub prices upward. A coal plant whose margins were unattractive at $3/MMBtu Henry Hub looks much better at $4.50. But for now, more than 30 GW of retirements are still planned for 2026-30 (pink bars).

Figure 1 | Planned and actual US coal retirements

Prospects for 2026 retirements

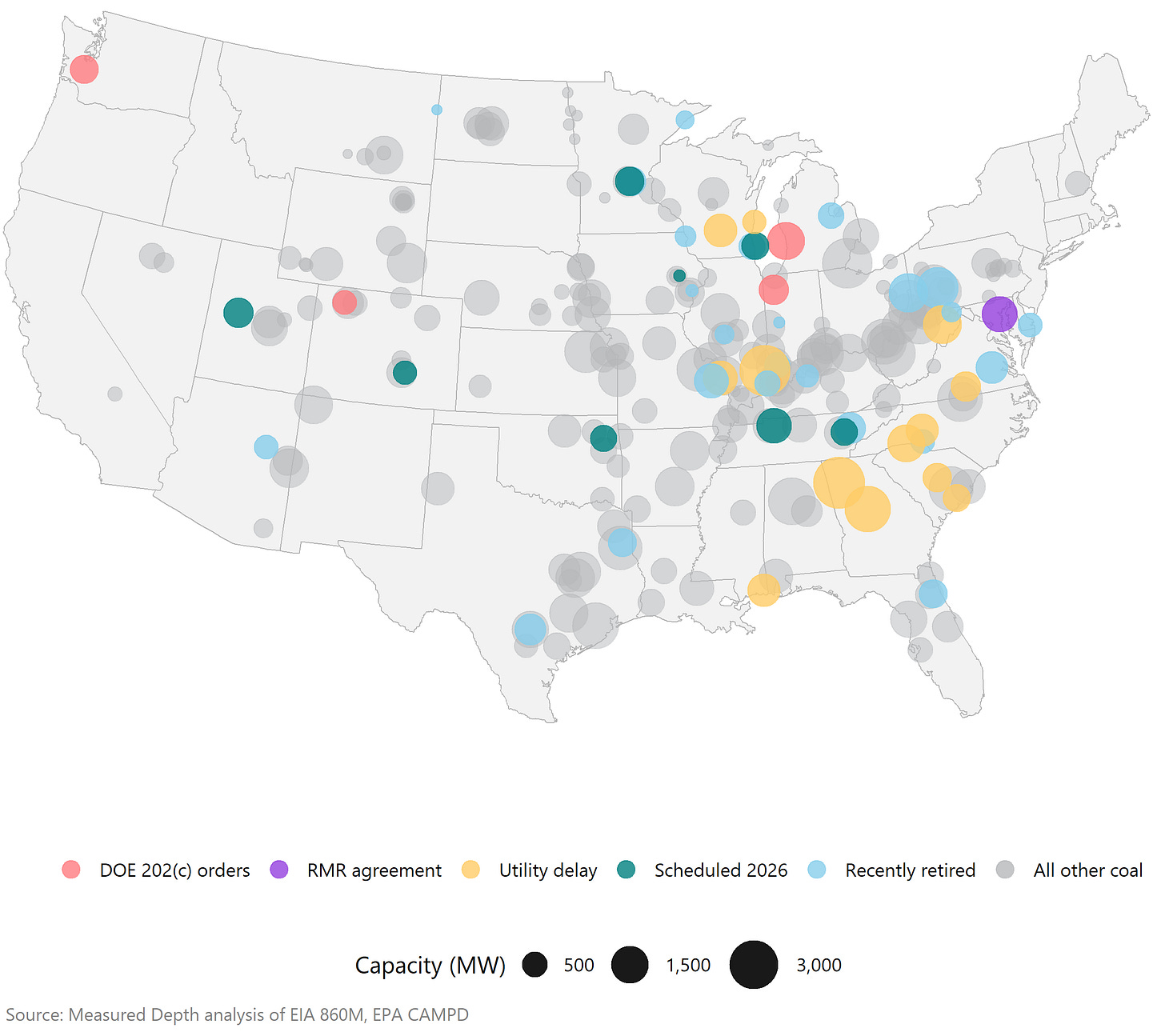

Beyond those changes to fundamentals, the election of Donald Trump in 2024 gave utilities political cover to delay retirements, and the Department of Energy issued 202(c) orders requiring ~3.7 GW of scheduled coal retirements1 to remain online. I was admittedly skeptical of the administration’s delays, ascribing it to Trump’s cultural emphasis on coal mining.2

In its orders, the DOE cites a NERC reliability study, but reliability is the ISO/RTOs’ job, not the DOE’s. At the very least, the 202(c) orders are an unusual federal intervention into regional market operations. And ISO/RTOs have exercised this authority recently: PJM, Maryland regulators, and the plant owner Talen reached a reliability must-run settlement to keep the Brandon Shores plant in Maryland online through 2029.

But the DOE’s decisions weren’t purely political; they were spread across states, not just in those run by Democrats. While the administration likely wants to make a political point with the delays, my analysis confirms that the decisions weren’t arbitrary. The DOE both permitted many other coal retirements to proceed in the same markets and targeted plants with limited replacement capacity, particularly in peak months.

That raises an uncomfortable question: if the ISO/RTOs are responsible for reliability, why did it take a DOE order to keep these plants online? The answer likely lies in capacity market design, which nearly everyone agrees is broken in one way or another. Regardless, the fact that the DOE felt compelled to act — and wasn’t obviously wrong to do so — is itself a signal of how stressed the system has become. The DOE’s 202(c) orders are best understood as a late-stage symptom of reliability stress.

That debate around capacity market design is beyond the scope of this post. Instead, I evaluate the likelihood that the DOE delays — issued shortly before the plants’ scheduled retirements and lasting only 90 days — will be extended, and that scheduled 2026 retirements will proceed as planned.

Figure 2 | US coal capacity3

Why annual utilization is the wrong metric

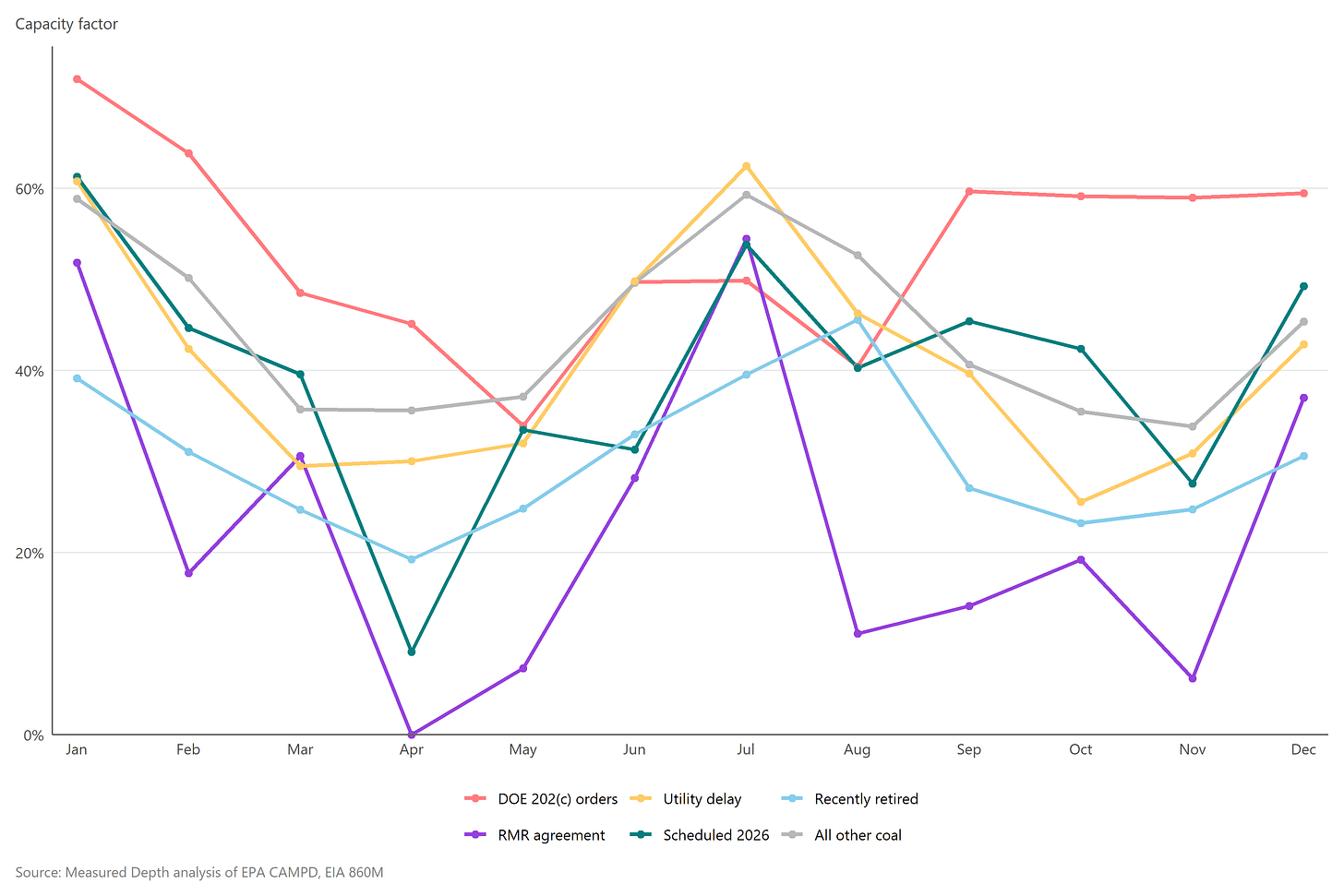

Average capacity factors help explain which plants have retired but will be less of a driver of which plants can retire going forward. The Talen RMR plant (purple line in Figure 3) operated at just a ~23% capacity factor over the last year, but it ramps up seasonally, highlighting that a plant can be essential during peak months even if its annual capacity factor appears marginal.

Interestingly, utilization of both the 202(c) plants (pink line) and the plants scheduled to retire this year (teal line) peaks in January. As more customers use electricity for home heating, coal plants become more important assets in winter than in summer, because gas generators must compete with gas LDCs not only for gas volumes but also for gas deliverability, often using the same pipeline capacity.

Figure 3 | Coal plant capacity factors for most recent operating year

Whether retirements are realistic depends not just on how necessary the coal plant is but also on the availability of replacement capacity. In some cases, retiring coal assets are being replaced by new gas capacity, but in others, the replacement load will need to come from existing assets, most likely existing coal or CC units.

Across the United States, weighted-average combined-cycle utilization is only ~55%, with gas peaking and steam units running only about one-third and one-sixth as hard as CCs. However, CC utilization runs more than 65% in July and August, and is higher still in some regional markets.

Now, evaluating coal retirements means answering three questions:

When the plant runs, since annual averages obscure winter dependence

What replaces it during winter peaks, since capacity is different than deliverability

Whether that replacement has firm fuel access, since gas-on-paper is not gas-in-January

Applying this framework to the 2026 slate immediately narrows the field of plausible retirements. Next week, I’ll analyze them unit by unit and explain why I expect 3-5 GW to actually retire, not the 7+ GW currently on the books.

The DOE also did the same for the Wagner oil-fired plant and gas-fired Eddystone

“One thing I learned about the coal miners is that’s what they want to do. You could give them a penthouse on Fifth Avenue in a different kind of a job, but they’d be unhappy. They want to mine coal. That’s what they love to do.”

The EIA considers the Intermountain Power Project in Utah to have retired. The IPP coal units are no longer operating, but I include it in the planned retirements analysis because the plant is still grid-connected as mandated by the Utah legislature. This resolution may offer a more realistic path forward for some other coal units considering retirement.

Hi Amber, FYI-I also follow Rob West of Thunder Said Energy. He was on Close of Business Tuesday (COBT) podcast last week and stated that new coal mine development cost in India and China is increasing significantly. Rob state at about 35:00 minute mark that it would be cheaper for China and India to import LNG rather than develop new coal mines. I am not asking you to agree or disagree, but wanted you to be aware of his thoughts as you develop your LNG articles as his comments surprised me and seem to go against the conventional thought. I liked your last LNG article and I am thinking about your article and Rob’s podcast comment.