Who is still backstopping US LNG?

The buyers, contracts, and balance sheets behind 2025 FIDs

Despite bearish headwinds both from a strengthening Henry Hub and weakening global prices, 8 Bcfd of North American LNG capacity took FID in 2025. Unlike prior FID waves, these projects were underwritten primarily by LNG developers, North American E&Ps, and portfolio players — not LNG consumers.

That shift, in this cycle, turns North American LNG from a supply source into a vehicle for commodity risk.

Who is still offtaking US LNG?

LNG developers

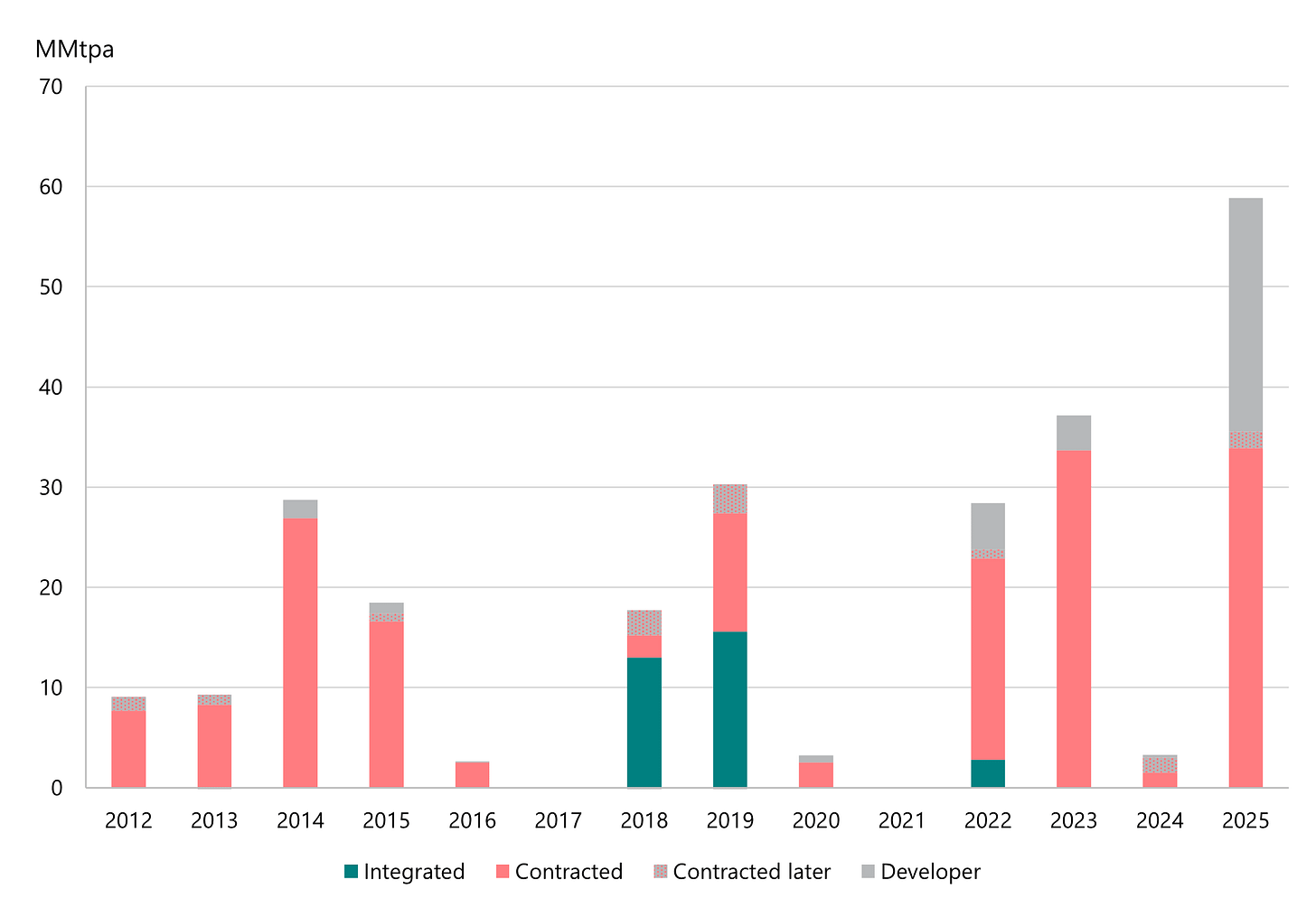

In 2025, ~60 MMtpa of North American liquefaction capacity took FID, about 60% higher than the previous record. Notably, the ~23 MMtpa of capacity that developers have not yet sold exceeds the unsold capacity1 of all previous North American FIDs combined.

Figure 1 | North American LNG FIDs by offtaker type

Louisiana LNG2 accounts for ~14 MMtpa of this unsold capacity, but even excluding this project, developers sold just ~78% of their capacity, down from ~88% over the 2012-24 period. As a group, developers are taking materially more commercial risk than in prior cycles.

Notably, Cheniere has adopted a more conservative posture. Cheniere contracted ~89% of the capacity for its 2012-15 FIDs but 100% at its Corpus Christi midscale expansion this year. This approach aligns with the company’s very bearish sentiment on LNG prices during its recent earnings call.

In contrast, NextDecade holds 2.9 MMtpa of capacity across the fourth and fifth trains at Rio Grande and Sempra 5.5 MMtpa at the Port Arthur expansion. Venture Global did not disclose how many trains comprise its CP2 phase 1 FID; however, regardless of whether it is fully contracted, the company retains commodity exposure through its extended pre-commissioning period.

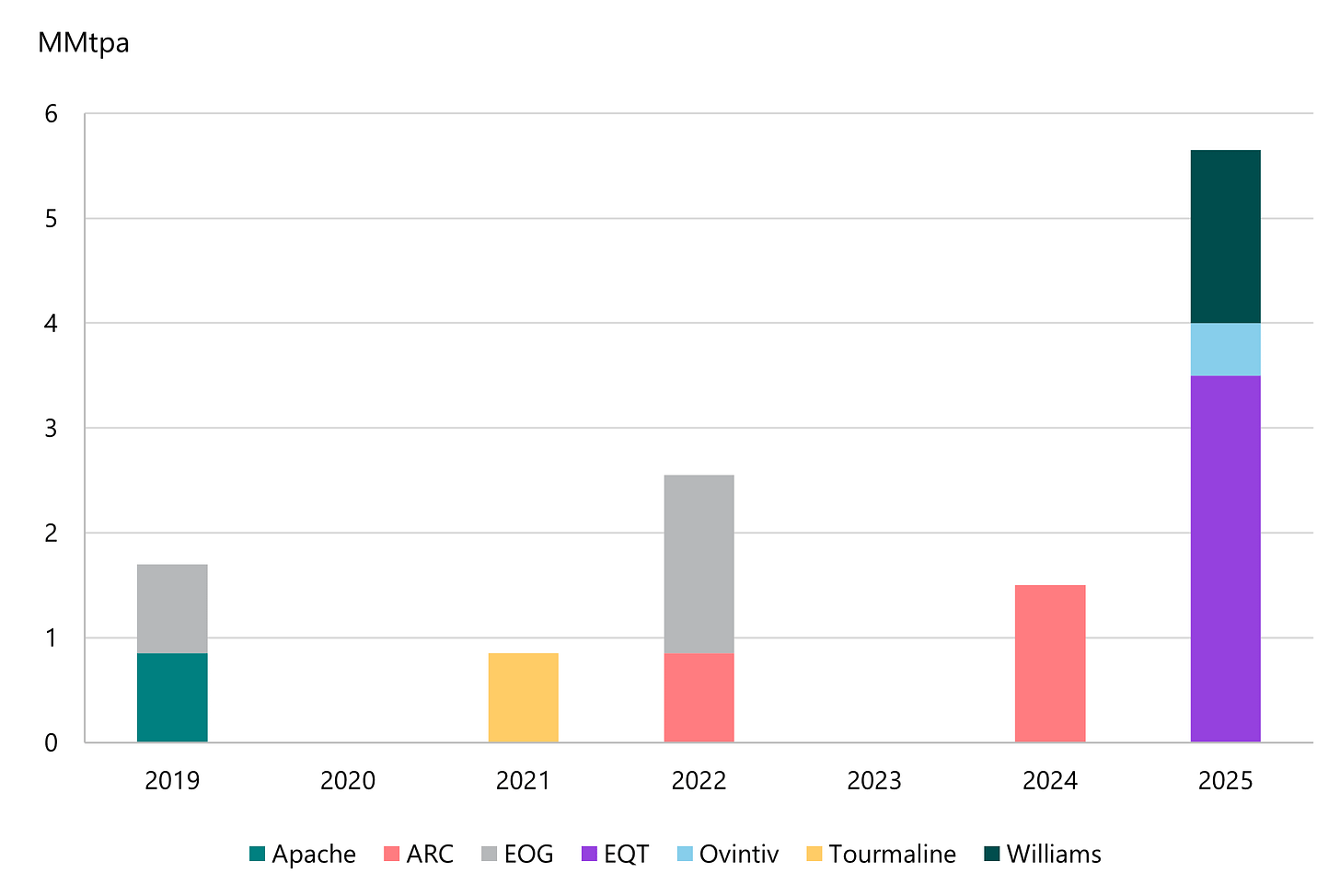

North American operators

North American operators also ramped up their LNG offtake in 2025. EQT was the most aggressive, contracting for 3.5 MMtpa between Rio Grande Train 5 and Port Arthur Phase 2. Williams positioned its LNG offtake more conservatively, as part of a deal that would benefit Transco and its Haynesville gathering assets. Ovintiv’s Cedar LNG offtake entails a different cost-benefit equation than Gulf Coast LNG, given transmission constraints from western Canada and the potential for AECO prices to remain weak even as Henry Hub prices rise.

Figure 2 | North American operator post-FID LNG offtake by contract year

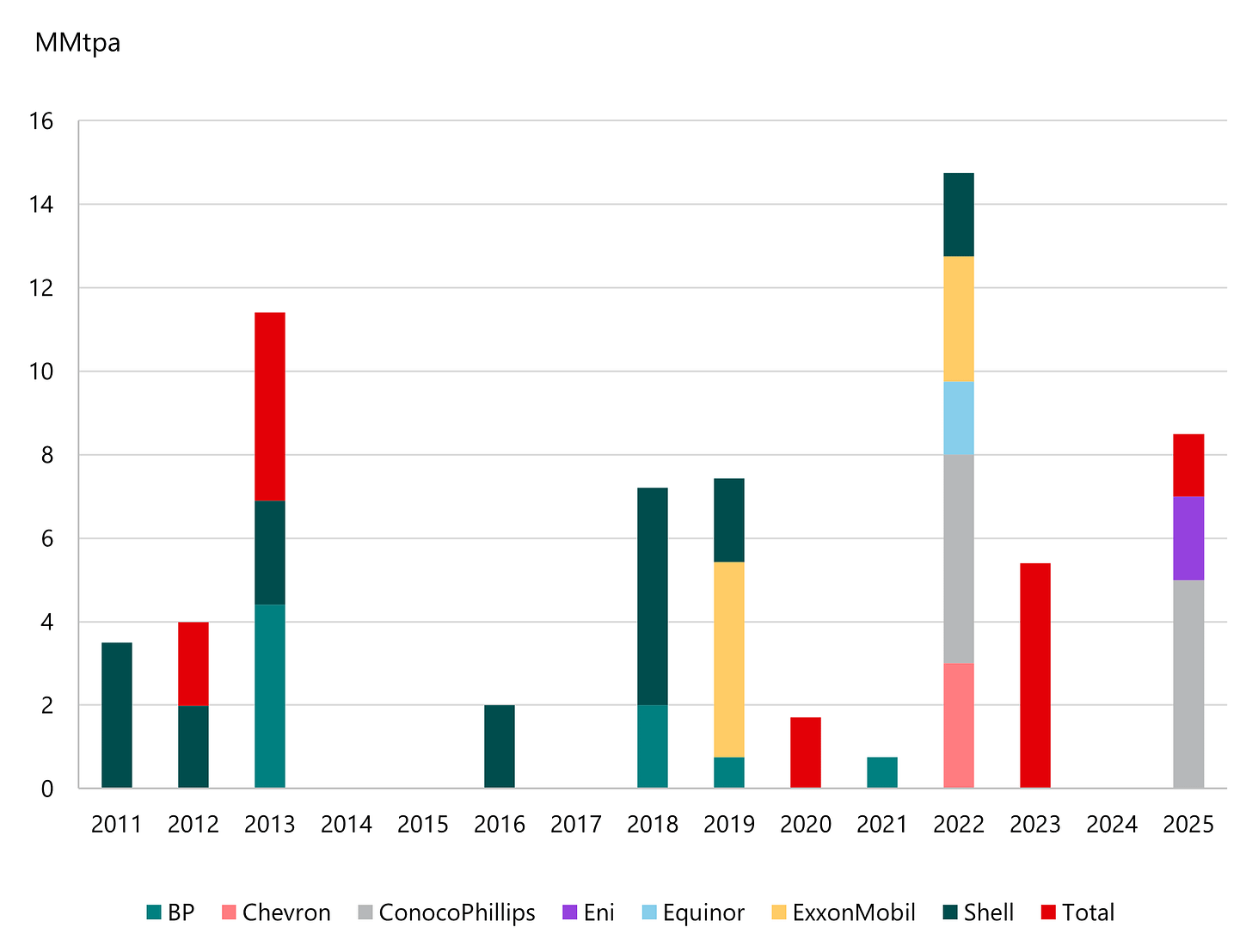

A changing set of portfolio players

BP and Shell — historically major offtakers — have not contracted for any North American LNG since 2022, with Shell’s CEO explicitly citing expected LNG oversupply.

This year’s portfolio buying saw the entry of Eni, with 2 MMtpa at CP2, while ConocoPhillips doubled its North American LNG exposure, adding 1 MMtpa at Rio Grande train 5 and 4 MMtpa at Port Arthur phase 2.

Figure 3 | Post-FID portfolio player North American LNG contracts by year

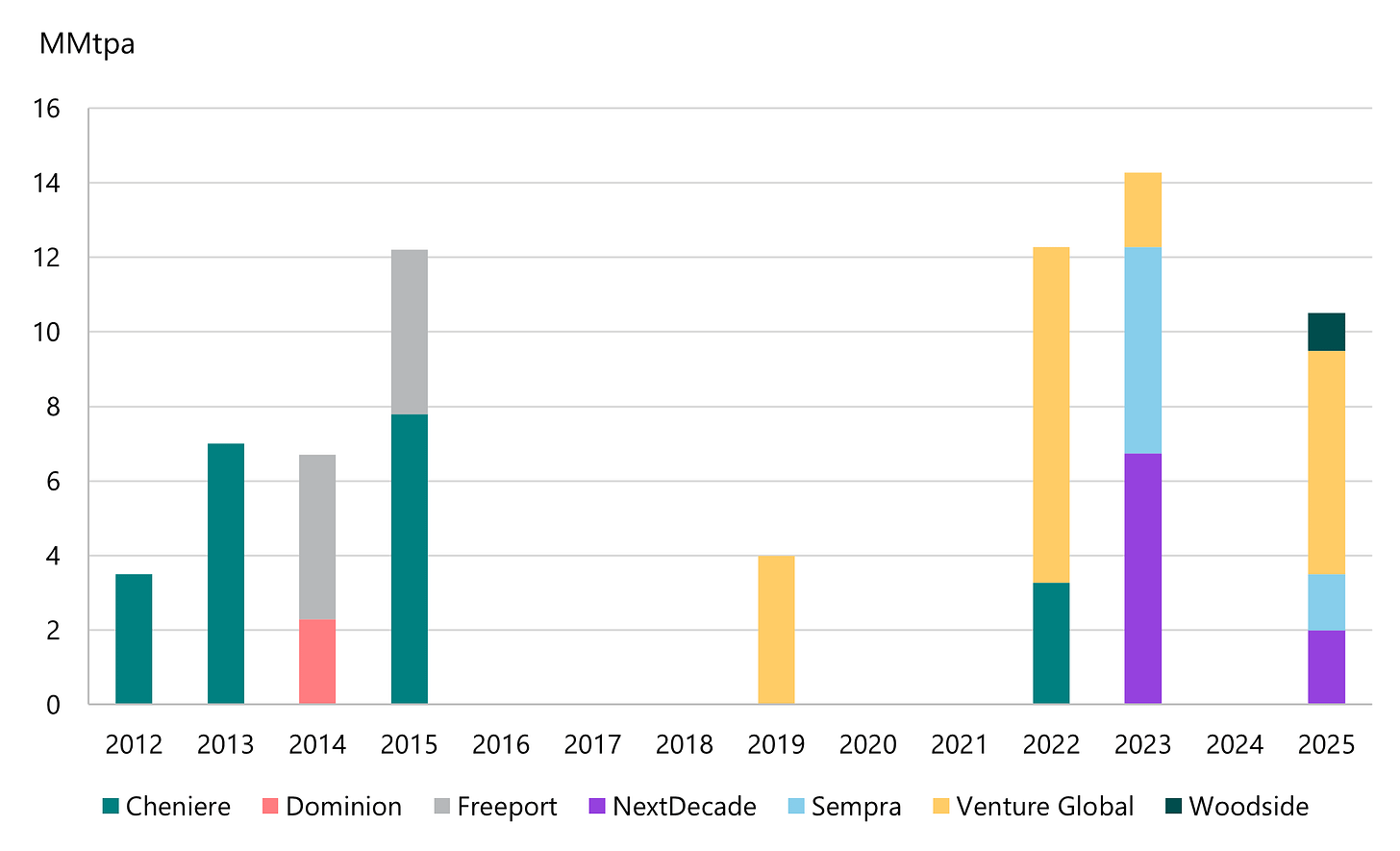

Some end users — as long as it’s cheap

Inasmuch as end-users are offtakers from 2025 North American LNG FIDs, their commitments were weighted toward the low-cost provider, Venture Global. This trend points to increasing price sensitivity among buyers and bearishness regarding the potential for sustained high global gas prices.

Figure 4 | End-user North American LNG contracts by project FID year

Why are they doing this?

US LNG offtakers pay a fixed liquefaction toll of $2-3/MMBtu for capacity and either incur additional fixed costs for pipeline capacity, LNG shipping, and regas, or accept a discount to global gas prices to compensate counterparties who do.

Committing to US LNG requires believing either that global prices sustainably clear near $11/MMBtu, or that Henry Hub remains structurally near $3 while global prices average closer to $10. Given the impending LNG oversupply, this is an exceptionally unfavorable point in the cycle to add US LNG exposure.

Other factors are also driving offtakers’ investments in North American LNG.

Right skew in global gas prices

Some developers emphasized the price upside during periods of market tightness. They argue that, even if US LNG fails to recover full-cycle costs most years, the right skew in global gas prices can offset these losses: $1/MMBtu underwater most years, $15/MMBtu in-the-money once a decade, and the option still pencils out. In its earnings call, Woodside made this argument:

We see the asymmetric skew in gas pricing. When there is an energy shortage, LNG serves as a flexible and mobile solution. During this period, our ability to direct uncommitted volumes to the optimal market gave us the edge to extract further value

Past examples include Fukushima and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Future disruptions are more likely to come from shipping chokepoints or Middle Eastern geopolitical risk.

E&Ps frame LNG similarly, as a means to smooth realized prices across cycles. But at demand charges of $2.40-2.90/MMBtu, US LNG is an extremely expensive option. Companies that resist chasing the last five years of stronger LNG prices relative to Henry Hub are likely to fare better, much as gas E&Ps that resisted rushing into oil acreage in the 2010s ultimately did.

A portfolio approach: being the final contract to get another project over the line

In the 2010s, US producers backstopped domestic gas pipeline investment not because the FT itself would be profitable but because relieving basin constraints lifted realized prices on the rest of their production.

If a US E&P contracts for 1 MMtpa of capacity — especially if the commitment enables FID — it may facilitate ~1.5 Bcfd of incremental demand at the expense of losses on ~150 MMcfd of gas sales. But the “portfolio impact” argument for LNG offtake is weaker, because producers are not existentially constrained in the way that single-basin operators are without pipeline takeaway. Domestic demand is growing, and a given E&P is unlikely to realize much of the incremental 1.5 Bcfd.

They can do it now and might not be able to later

In its recent earnings call, NextDecade highlighted rising competition for turbines and other equipment between LNG and power projects:

Schedules to build right now now are 100% correlated to their ability to get the equipment that competes with power gen: turbines, transformers, everything. And it’s moving farther and farther to the right on the timeline. ... People who have not locked up their turbines, right now are not looking at starting up in 2031.

Conversely, having turbines locked up and not building them means foregoing a speed-to-market advantage.

A less discussed3 driver is political risk. Many fear that future Democratic administrations could again restrict LNG permitting, as former US President Joe Biden myopically did in 2024. But to fear future permitting disruptions is to miss the changes in the Democratic Party since then:

Climate change receding from the party’s agenda, in favor of healthcare

A meaningful contingent of House Democrats joined Republicans to pass the SPEED Act to streamline energy development

The oil and gas industry does not yet believe this, to the extent that firms are investing in US LNG offtake at least partly because they don’t expect to have that option in the future.

Matching markets for their gas

One large US E&P CFO described LNG offtake to me as matching the markets for their gas, arguing that if ~20% of US production is consumed globally, then ~20% of their volumes should be exposed to global pricing.

My perspective is different. US liquefaction capacity is likely to be fully utilized, so matching the markets for their gas should mean selling ~20% of their volume to the Chenieres and Venture Globals, not taking LNG offtake risk directly.

Additionally, even optimistic LNG timelines imply first cargoes four4 years out, while only the next seven years meaningfully impact E&P net asset valuations. LNG offtake is a long-dated commitment with limited valuation impact — especially if global LNG markets remain oversupplied late this decade.

What’s different this time

The defining feature of the 2025 LNG FID wave was not its size but its composition. Unlike in prior cycles, most of the capacity was not underwritten by end users locking in supply but by new players taking commercial exposure.

Some of this risk may pay off over the long run. But with global LNG markets likely oversupplied through much of the next decade, these commitments are more likely to weigh on returns than to enhance them. The projects will almost certainly be built and utilized — but utilization does not imply profitability.

This includes capacity that was unsold at the time of FID but subsequently contracted

In this analysis, I’ve excluded integrated projects such as LNG Canada and Golden Pass because the companies involved have non-North American LNG portfolios. In contrast, Cheniere, Venture Global, and Sempra have LNG marketing divisions, but these functions primarily support their infrastructure businesses. Louisiana LNG could be considered an integrated project, but I classify it otherwise here, principally because Woodside has indicated its intention to sign Louisiana LNG offtake contracts specifically, rather than portfolio LNG contracts generally.

Publicly, at least

Venture Global projects are typically online faster, but with an extended commissioning period, which means offtakers don’t see their LNG until much later